index.md 21KB

title: Linked Data - Design Issues

url: https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html

hash_url: 8df6b7af9a

Linked Data

The Semantic Web isn't just about putting data on the web. It is about making links, so that a person or machine can explore the web of data. With linked data, when you have some of it, you can find other, related, data.

Like the web of hypertext, the web of data is constructed with documents on the web. However, unlike the web of hypertext, where links are relationships anchors in hypertext documents written in HTML, for data they links between arbitrary things described by RDF,. The URIs identify any kind of object or concept. But for HTML or RDF, the same expectations apply to make the web grow:

-

Use URIs as names for things

-

Use HTTP URIs so that people can look up those names.

-

When someone looks up a URI, provide useful information, using the standards (RDF*, SPARQL)

-

Include links to other URIs. so that they can discover more things.

Simple. In fact, though, a surprising amount of data isn't linked in 2006, because of problems with one or more of the steps. This article discusses solutions to these problems, details of implementation, and factors affecting choices about how you publish your data.

The four rules

I'll refer to the steps above as rules, but they are expectations of behavior. Breaking them does not destroy anything, but misses an opportunity to make data interconnected. This in turn limits the ways it can later be reused in unexpected ways. It is the unexpected re-use of information which is the value added by the web.

The first rule, to identify things with

URIs, is pretty much understood by most

people doing semantic web technology. If it doesn't use the

universal URI set of symbols, we don't call it

Semantic Web.

The second rule, to use HTTP

URIs, is also widely understood. The

only deviation has been, since the web started, a constant

tendency for people to invent new URI schemes (and

sub-schemes within the urn: scheme) such as

LSIDs and handles and XRIs and

DOIs and so on, for various reasons.

Typically, these involve not wanting to commit to the

established Domain Name System (DNS) for

delegation of authority but to construct something under separate

control. Sometimes it has to do with not understanding

that HTTP URIs are names (not

addresses) and that HTTP name lookup is a complex,

powerful and evolving set of standards. This issue discussed at

length elsewhere, and time does not allow us to delve into it

here. [ @@ref TAG finding, etc])

The third rule, that one should serve information on the web against a URI, is, in 2006, well followed for most ontologies, but, for some reason, not for some major datasets. One can, in general, look up the properties and classes one finds in data, and get information from the RDF, RDFS, and OWL ontologies including the relationships between the terms in the ontology.

The basic format here for RDF/XML, with its popular alternative serialization N3 (or Turtle). Large datasets provide a SPARQL query service, but the basic linked data should br provided as well.

Many research and evaluation projects in the few years of the Semantic Web technologies produced ontologies, and significant data stores, but the data, if available at all, is buried in a zip archive somewhere, rather than being accessible on the web as linked data. The Biopax project, the CSAktive data on computer science research people and projects were two examples. [The CSAktive data is now (2007) available as linked data]

There is also a large and increasing amount of URIs of non-ontology data which can be looked up. Semantic wikis are one example. The "Friend of a friend" (FOAF) and Description of a Project (DOAP) ontologies are used to build social networks across the web. Typical social network portals do not provide links to other sites, nor expose their data in a standard form.

LiveJournal and Opera Community are two portal web sites which do in fact publish their data in RDF on the web. (Plaxo has a trail scheme, and I'm not sure whether they support knows links). This means that I can write in my FOAF file that I know Håkon Lie by using his URI in the Opera Community data, and a person or machine browsing that data can then follow that link and find all his friends. [Update:] Also, the Opera Community site allows you to register the RDF URI for yourelf on another site. This means that public data about you from different sites can be linked together into one web, and a person or machine starting with your Opera identity can find the others.

The fourth rule, to make links elsewhere, is necessary to connect the data we have into a web, a serious, unbounded web in which one can find al kinds of things, just as on the hypertext web we have managed to build.

In hypertext web sites it is considered generally rather bad etiquette not to link to related external material. The value of your own information is very much a function of what it links to, as well as the inherent value of the information within the web page. So it is also in the Semantic Web.

So let's look at the ways of linking data, starting with the simplest way of making a link.

Basic web look-up

The simplest way to make linked data is to use, in one file, a URI which points into another.

When you write an RDF file, say <http://example.org/smith>, then you can use local identifiers within the file, say #albert, #brian and #carol. In N3 you might say

<#albert> fam:child <#brian>, <#carol>.

or in RDF/XML

<rdf:Description about="#albert"

<fam:child rdf:Resource="#brian">

<fam:child rdf:Resource="#carol">

</rdf:Description>

The WWW architecture now gives a global identifier "http://example.org/smith#albert" to Albert. This is a valuable thing to do, as anyone on the planet can now use that global identifier to refer to Albert and give more information.

For example, in the document <http://example.org/jones> someone might write:

<#denise> fam:child <#edwin>, <smith#carol>.

or in RDF/XML

<rdf:Description about="#denise"

<fam:child rdf:Resource="#edwin">

<fam:child rdf:Resource="http://example.org/smith#carol">

</rdf:Description>

Clearly it is reasonable for anyone who comes across the

identifier 'http://example.org/smith#carol" to:

- Form the URI of the document by truncating before the hash

- Access the document to obtain information about #carol

We call this dereferencing the URI. This is basic semantic web.

There are several variations.

Variation: URIs without Slashes and HTTP 303

There are some circumstances in which dividing identifiers into documents doesn't work very well. There may logically be one global symbol per document per document, and there is a reluctance to include a # in the URI such as

http://wordnet.example.net/antidisesablishmentarianism#word

Historically, the early Dublin Core and FOAF vocabularies did not have # in their URIs. In any event when HTTP URIs without hashes are used for abstract concepts, and there is a document that carries information about them, then:- An HTTP GET request on the URI of the concept returns 303 See Also and gives in the Location: header, the URI of the document.

- The document is retrieved as normal

This method has the advantage that URIs can be made up of all forms. It has the disadvantage that an HTTP request mBrowse-ableust be made for every single one. In the case of Dublin Core, for example, dc:title and dc:creator etc are in fact served by the same ontology document, but one does not know until they have each been fetched and returned HTTP redirections.

Variation: FOAF and rdfs:seeAlso

The Friend-Of-A-Friend convention uses a form of data link, but not using either of the two forms mentioned above. To refer to another person in a FOAF file, the convention was to give two properties, one pointing to the document they are described in, and the other for identifying them within that document.

<#i> foaf:knows [

foaf:mbox <mailto:joe@example.com>;

rdfs:seeAlso <http://example.com/foaf/joe> ].

Read, "I know that which has email joe@example.com and about which more information is in <http://example.com/foafjoe>".

In fact, for privacy, often people don't put their email addresses on the web directly, but in fact put a one-way hash (SHA-1) of their email address and give that. This clever trick allows people who know their email address already to work out that it is the same person, without giving the email away to others.

<#i> foaf:knows [

foaf:mbox_sha1sum "2738167846123764823647"; # @@ dummy

rdfs:seeAslo <http://example.com/foaf/joe> ].

This linking system was very successful, forming a growing social network, and dominating, in 2006, the linked data available on the web.

However, the system has the snag that it does not give URIs to people, and so basic links to them cannot be made.

I recommend (e.g in weblogs on Links on the Semantic Web , Give yourself a URI, and and Backward and Forward links in RDF just as important) that those making a FOAF file give themselves a URI as well as using the FOAF convention. Similarly, when you refer to a FOAF file which gives a URI to a person, use it in your reference to that person, so that clients which just use URIs and don't know about the FOAF convention can follow the link.

So now we have looked at ways of making a link,

let’s look at the choices of when to make a link.

One important pattern is a set of data which you can explore as you go link by link by fetching data. Whenever one looks up the URI for a node in the RDF graph, the server returns information about the arcs out of that node, and the arcs in. In other words, it returns any RDF statements in which the term appears as either subject or object.

Formally, call a graph G browsable if, for the URI of any node in G, if I look up that URI I will be returned information which describes the node, where describing a node means:

- Returning all statements where the node is a subject or object; and

- Describing all blank nodes attached to the node by one arc.

(The subgraph returned has been referred to as "minimum Spanning Graph (MSG [@@ref] ) or RDF molecule [@@ref], depending on whether nodes are considered identified if they can be expressed as a path of function, or reverse inverse functional properties. A concise bounded description, which only follows links from subject to object, does not work.)

In practice, when data is stored in two documents, this means that any RDF statements which relate things in the two files must be repeated in each. So, for example, in my FOAF page I mention that I am a member of the DIG group, and that information is repeated on the DIG group data. Thus, someone starting from the concept of the group can also find out that I am a member. In fact, someone who starts off with my URI can find all the people who are in the same group.

Limitations on browseable data

So statements which relate things in the two documents must be repeated in each. This clearly is against the first rule of data storage: don't store the same data in two different places: you will have problems keeping it consistent. This is indeed an issue with browsable data. A set of of completely browsable data with links in both directions has to be completely consistent, and that takes coordination, especially if different authors or different programs are involved.

We can have completely browsable data, however, where it is automatically generated. The dbview server, for example, provides a browsable virtual documents containing the data from any arbitrary relational database.

When we have a data from multiple sources, then we have compromises. These are often settled by common sense, asking the question,

"If someone has the URI of that thing, what relationships to what other objects is it useful to know about?"

Sometimes, social questions determine the answer. I have links in my FOAF file that I know various people. They don't generally repeat that information in their FOAF files. Someone may say that they know me, which is an assertion which, in the FOAF convention, is theirs to assert, and the reader's to trust or not.

Other times, the number of arcs makes it impractical. A GPS track gives thousands of times at which my latitude, longitude are known. Every person loading my FOAF file can expect to get my business card information, but not all those trackpoints. It is reasonable to have a pointer from the track (or even each point) to the person whose position is represented, but not the other way.

One pattern is to have links of a certain property in a separate document. A person's homepage doesn't list all their publications, but instead puts a link to it a separate document listing them. There is an understanding that foaf:made gives a work of some sort, but foaf:pubs points to a document giving a list of works. Thus, someone searching for something foaf:made link would do well to follow a foaf:pubs link. It might be useful to formalize the notion with a statement like

foaf:made link:listDocumentProperty foaf:pubs.

in one of the ontologies.

Query services

Sometimes the sheer volume of data makes serving it as lots of files possible, but cumbersome for efficient remote queries over the dataset. In this case, it seems reasonable to provide a SPARQL query service. To make the data be effectively linked, someone who only has the URI of something must be able to find their way the SPARQL endpoint.

Here again the HTTP 303 response can be used, to refer the enquirer to a document with metadata about which query service endpoints can provide what information about which classes of URIs.

Vocabularies for doing this have not yet been standardized.(Added 2010). This year, in order to encourage people -- especially government data owners -- along the road to good linked data, I have developped this star rating system.

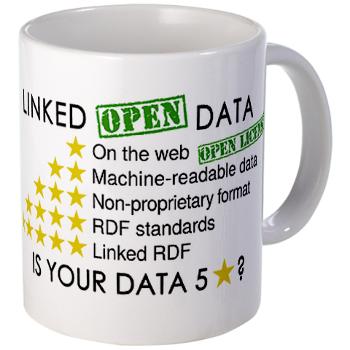

Linked Data is defined above. Linked Open Data (LOD) is Linked Data which is released under an open licence, which does not impede its reuse for free. Creative Commons CC-BY is an example open licence, as is the UK's Open Government Licence. Linked Data does not of course in general have to be open -- there is a lot of important use of lnked data internally, and for personal and group-wide data. You can have 5-star Linked Data without it being open. However, if it claims to be Linked Open Data then it does have to be open, to get any star at all.

Under the star scheme, you get one (big!) star if the information has been made public at all, even if it is a photo of a scan of a fax of a table -- if it has an open licence. The you get more stars as you make it progressively more powerful, easier for people to use.| ★ | Available on the web (whatever format) but with an open licence, to be Open Data |

| ★★ | Available as machine-readable structured data (e.g. excel instead of image scan of a table) |

| ★★★ | as (2) plus non-proprietary format (e.g. CSV instead of excel) |

| ★★★★ | All the above plus, Use open standards from W3C (RDF and SPARQL) to identify things, so that people can point at your stuff |

| ★★★★★ | All the above, plus: Link your data to other people’s data to provide context |

How well does your data do? You can buy 5 star data mugs, T-shirts and bumper stickers from the W3C shop at cafepress: use them to get your colleages and fellows conference-goers thinking 5 star linked data. (Profits also help W3C :-).

Now in 2010, people have been pressing me, for governmet data, to add a new requirement, and that is there should be metadata about the data itself, and that that metadata should be availble from a major catalog. Any open dataset (or even datasets which are not but should be open) can be regisetreed at ckan.net. Government datasets from the UK and US hsould be regisetred at data.gov.uk or data.gov respectively. Other copuntries I expect to develop their own registries. Yes, there should be metadata about your dataset. That may be the subject of a new note in this series.

Linked data is essential to actually connect the semantic web. It is quite easy to do with a little thought, and becomes second nature. Various common sense considerations determine when to make a link and when not to.

The Tabulator client (running in a suitable browser) allows you to browse linked data using the above conventions, and can be used to check that your linked data works.

References

[Ding2005] Li Ding, et. al., Tracking RDF Graph Provenance using RDF Molecules, UMBC Tech Report TR-CS-05-06

Followup

2006-02 Rob Crowell adapts Dan Connolly's DBView (2004) which maps SQL data into linked RDF, adding backlinks.

2006-09-05 Chris Bizer et al adapt D2R Server to provide a linked data view of a database.

2006-10-10 Chris Bizer et al produce the Semantic Web Client Library, "Technically, the library represents the Semantic Web as a single Jena RDF graph or Jena Model." The code feteches web documents as needed to answer queries.

2007-01-15 Yves Raimond has produced a Semantic Web client for SWI prolog wit similar functionality.

I have a talk at the 2009 O'Reilly eGovernment 2.0 conference in Washington DC, talking about "Just a Bag of Chips" @@ref, and talking about the 5 star scheme. Following that, From InkDroid blogged summary (and CSS) of my 5 star sceheme adapted here