index.md 13KB

title: Every line of code is always documented

url: https://mislav.net/2014/02/hidden-documentation/

hash_url: d92f0d3996

Every line of code comes with a hidden piece of documentation.

Whoever wrote line 4 of the following code snippet decided to access the

clientLeft property of a DOM node for some reason, but do nothing with the

result. It’s pretty mysterious. Can you tell why they did it, or is it safe to

change or remove that call in the future?

1 // ...

2 if (duration > 0) this.bind(endEvent, wrappedCallback)

3

4 this.get(0).clientLeft

5

6 this.css(cssValues)If someone pasted you this code, like I did here, you probably won’t be able to tell who wrote this line, what was their reasoning, and is it necessary to keep it. However, most of the time when working on a project you’ll have access to its history via version control systems.

A project’s history is its most valuable documentation.

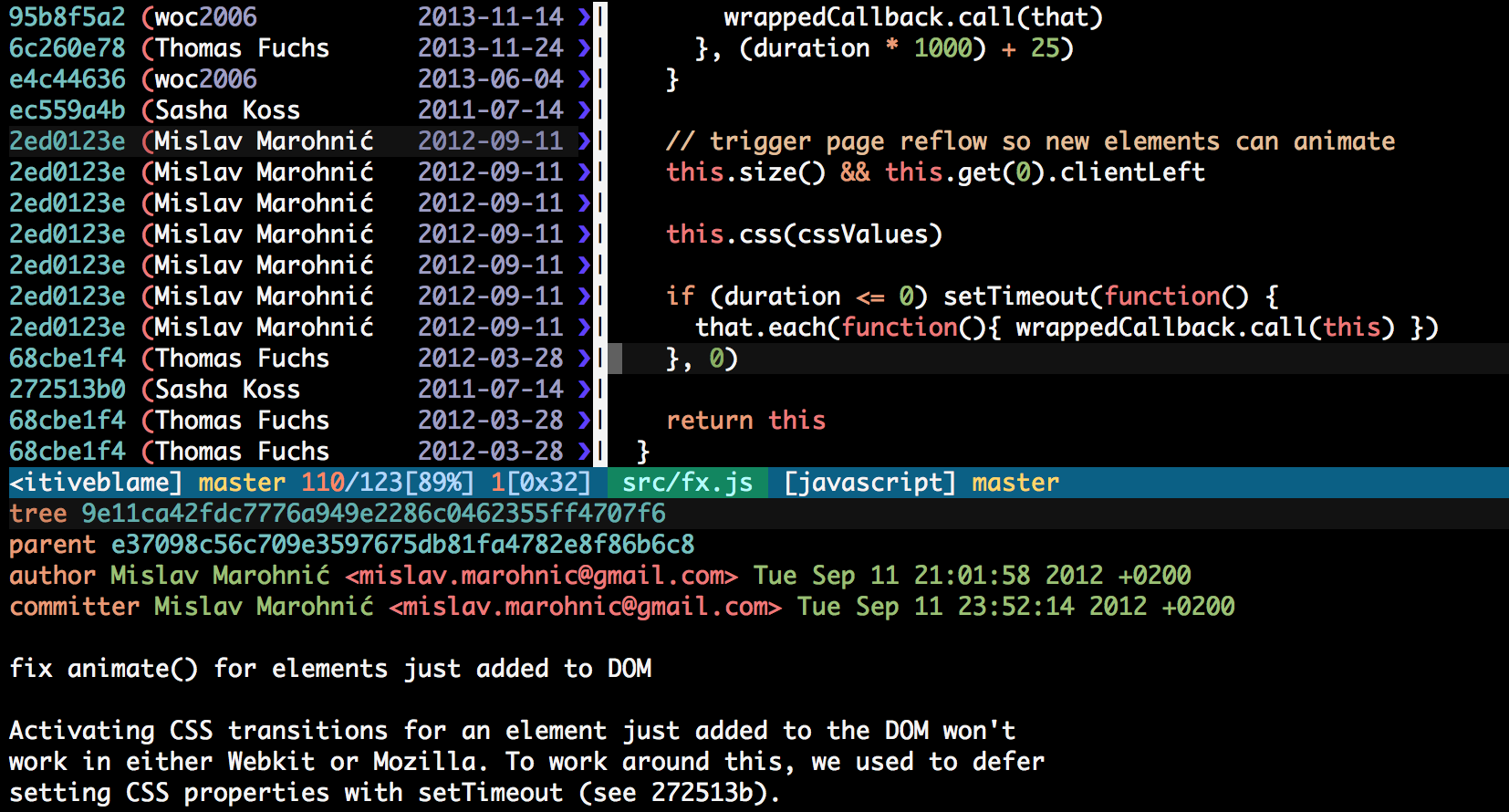

The mystery ends when we view the commit message which introduced this line:

$ git show $(git blame example.js -L 4,4 | awk '{print $1}')Fix animate() for elements just added to DOM

Activating CSS transitions for an element just added to the DOM won’t work in either Webkit or Mozilla. To work around this, we used to defer setting CSS properties with setTimeout (see

272513b).This solved the problem for Webkit, but not for latest versions of Firefox. Mozilla seems to need at least 15ms timeout, and even this value varies.

A better solution for both engines is to trigger “layout”. This is done here by reading

clientLeftfrom an element. There are other properties and methods that trigger layout; see gent.ilcore.com/2011/03/how-not-to-trigger-layout-in-webkit

As it turns out, this line—more specifically, the change which introduced this line—is heavily documented with information about why it was necessary, why did the previous approach (referred to by a commit SHA) not work, which browsers are affected, and a link for further reading.

As it also turns out, the author of that mysterious line was me. There are

ways I could have written that code itself better: by encapsulating the magic

property access in a function with an intention-revealing name such as

triggerLayout(), or at least by adding a code comment with a short

explanation that this kicks off the animation. For whatever reason, I might have

failed that day to make this particular code expressive. Code happens, and

it’s not always perfect.

Even if this code was more expressive or if it had contained lines of code comments, a project’s history will be able to provide even richer information:

- Who added this code;

- When did they add this code;

- Which was the accompanying test (if any);

- The full commit message can be a whole novel (while code comments should be kept succinct).

Code quality still matters a lot. But when pondering how you could improve your coding even further, you should consider aiming for better commit messages. You should request this not just from yourself, but from your entire team and all the contributors. The story of a software matters as much as its latest checkout.

Effective spelunking of project’s history

git blame

I’ve already demonstrated how to use git blame from the command line above.

When you don’t have access to the local git repository, you can also open the

“Blame” view for any file on GitHub.

A very effective way of exploring a file’s history is with Vim and Fugitive:

- Use

:Gblamein a buffer to open the blame view; - If you need to go deeper, press Shift-P on a line of blame pane to re-blame at the parent of that commit;

- Press o to open a split showing the commit currently selected in the blame pane.

- Use

:Gbrowsein the commit split to open the commit in the GitHub web interface; - Press gq to close the blame pane and return to the main buffer.

See :help Gblame for more information.

Find the pull request where a commit originated

With git blame you might have obtained a commit SHA that introduced a change, but commit messages don’t always carry enough information or context to explain the rationale behind the change. However, if the team behind a project practices GitHub Flow, the context might be found in the pull request discussion:

$ git log --merges --ancestry-path --oneline <SHA>..origin | tail

...

bc4712d Merge pull request #42 from sticky-sidebar

3f883f0 Merge branch 'master' into sticky-sidebarHere, a single commit SHA was enough to discover that it originated in pull request #42.

The git pickaxe

Sometimes you’ll be trying to find something that is missing: for instance, a

past call to a function that is no longer invoked from anywhere. The best way to

find which commits have introduced or removed a certain keyword is with the

‘pickaxe’ argument to git log:

$ git log -S<string>

This way you can dig up commits that have, for example, removed calls to a specific function, or added a certain CSS classname.

git churn

It’s possible to get valuable insight from history of a project not only by

viewing individual commits, but by analyzing sets of changes as a whole. For

instance, git-churn is a simple but valuable script that wraps

git log to compile stats about which files change the most. For example, to

see where the development of an app was focused on in the past 6 months:

$ git churn --since='6 months ago' app/ | tail

Incidentally, such analysis also highlights potential problems with technical debt in a project. A specific file changing too often is generally a red flag, since it probably means that the code in that file either needed to be frequently fixed for bugs, or that the file holds too much responsibility in general and should be split into smaller units.

Similar methods of history analysis can be employed to see which people were responsible recently for development of a certain part of the codebase. For instance, to see who contributed most often to the API part of an application:

$ git log --format='%an' --since='6 months ago' app/controllers/api/ | \

sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | head

109 Edmond Dantès

13 Jonathan Livingston

7 Ebanezer Scrooge

Being on the right side of history

Keep in mind that everything that you’re making today is going to enter the project’s history and stay there forever. To be nicer to other people who work with you (even if it’s a solo project, that includes yourself in 3 months), follow these ground rules when making commits:

Always write commit messages as if you are explaining the change to a colleague sitting next to you who has no idea of what’s going on. Per Thoughtbot’s tips for better commit messages:

Answer the following questions:

- Why is this change necessary?

- How does it address the issue?

- What side effects does this change have?

- Consider including a link [to the discussion.]

Avoid unrelated changes in a single commit. You might have spotted a typo or did tiny code refactoring in the same file where you made some other changes, but resist the temptation to record them together with the main change unless they’re directly related.

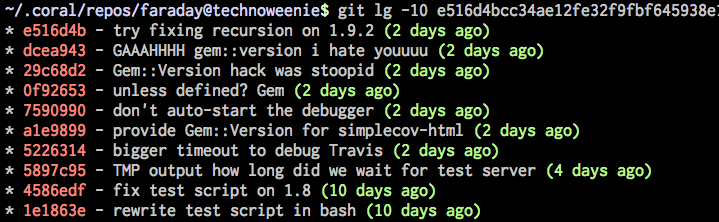

Always be cleaning up your history before pushing. If the commits haven’t been shared yet, it’s safe to rebase the heck out of them. The following could have been permanent history of the Faraday project, but I squashed it down to only 2 commits and edited their messages to hide the fact I had troubles setting the script up in the first place:

Corollary of avoiding unrelated changes: stick to a line-based coding style that allows you to append, edit or remove values from lists without changing adjacent lines. Some examples:

var one = "foo" , two = "bar" , three = "baz" // Comma-first style allows us to add or remove a // new variable without touching other lines # Ruby: result = make_http_request( :method => 'POST', :url => api_url, :body => '...', // Ruby allows us to leave a trailing comma, making it ) // possible to add/remove params while not touching othersWhy would you want to use such coding styles? Well, always think about the person who’s going to

git blamethis. In the JavaScript example, if you were the one who added a committed the value"baz", you don’t want your name to show up when somebody blames the line that added"bar", since the two variables might be unrelated.

Bonus script

Since you’ve read this far, I’ll reward you with an extra script. I call it git-overwritten and it shows blame information about original authors of lines changed or removed in a given branch:

$ git overwritten feature origin/master

28 2014-02-04 1fb2633 Mislav Marohnić: Add Makefile for building and testing 1 2014-01-13 b2d896a Jingwen Owen Ou: Add -t to mktemp in script/make 17 2014-01-07 385ccee Jingwen Owen Ou: Add script/make for homebrew build

This is useful when opening pull requests per GitHub Flow; you’ll want your

pull request reviewed by colleagues but you might not be sure who to ping. With

git-overwritten you’ll get the names of people who wrote the lines you just

changed, so you’ll know who to @-mention when opening a pull request.