index.md 25KB

title: The Bill Gates Line

url: https://stratechery.com/2018/the-bill-gates-line/

hash_url: 1d106e3927

Two of the more famous military sayings are “Generals are always preparing to fight the last war”, and “Never interrupt your enemy while he is making a mistake.” I thought of the latter at the conclusion of last Sunday’s 60 Minutes report on Google:

Google declined our request for an interview with one of its executives for this story, but in a written response to our questions, the company denied it was a monopoly in search or search advertising, citing many competitors including Amazon and Facebook. It says it does not make changes to its algorithm to disadvantage competitors and that, “our responsibility is to deliver the best results possible to our users, not specific placements for sites within our results. We understand that those sites whose ranking falls will be unhappy and may complain publicly.”

The 60 Minutes report was not exactly fair-and-balanced; it featured an anti-tech-monopoly crusader1, an anti-tech-monopoly activist, an anti-tech-monopoly regulator, and Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman. And, in what seems highly unlikely to have been a coincidence, Yelp this week filed a new antitrust complaint in the EU against Google. To be sure, just because a report was biased does not mean it was wrong; while I am a bit skeptical of the EU’s antitrust case against Google Shopping, the open case about Android seems pretty clear-cut. Neither, though, is Yelp’s direct concern.

Yelp’s Case Against Google

This is from a blog post about the 60 Minutes feature:

Yelp did participate in the piece because Google is doing the opposite of “delivering the best results possible,” and instead is giving its own content an unlawful advantage. We’ve made a video to explain exactly how Google puts its own interests ahead of consumers in local search, which you can watch here:

Yelp’s position, at least in this video, appears to be that Google’s answer box is anticompetitive because it only includes reviews and ratings from Google; presumably the situation could be resolved were Google to use sources like Yelp. There are three problems with this argument, though:

- First, the answer box originally included content scraped from sources like Yelp and other vertical search sites; under pressure from the FTC, driven in part by complaints from Yelp and other vertical search engines, Google agreed to stop doing so in 2013.2

- Second, in a telling testament to the power of being on top of search results, Google’s ratings and reviews have improved considerably in the two years since that video was posted; this isn’t a static market (to be sure, this is an argument that could be used on both sides).

- Third — and this is the point of this article — what Yelp seems to want will only serve to make Google stronger.

No wonder Google declined the request for an interview.

The Bill Gates Line

Over the last few weeks I have been exploring what differences there are between platforms and aggregators, and was reminded of this anecdote from Chamath Palihapitiya in an interview with Semil Shah:

Semil Shah: Do you see any similarities from your time at Facebook with Facebook platform and connect, and how Uber may supercharge their platform?

Chamath: Neither of them are platforms. They’re both kind of like these comical endeavors that do you as an Nth priority. I was in charge of Facebook Platform. We trumpeted it out like it was some hot shit big deal. And I remember when we raised money from Bill Gates, 3 or 4 months after — like our funding history was $5M, $83 M, $500M, and then $15B. When that 15B happened a few months after Facebook Platform and Gates said something along the lines of, “That’s a crock of shit. This isn’t a platform. A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it. Then it’s a platform.”

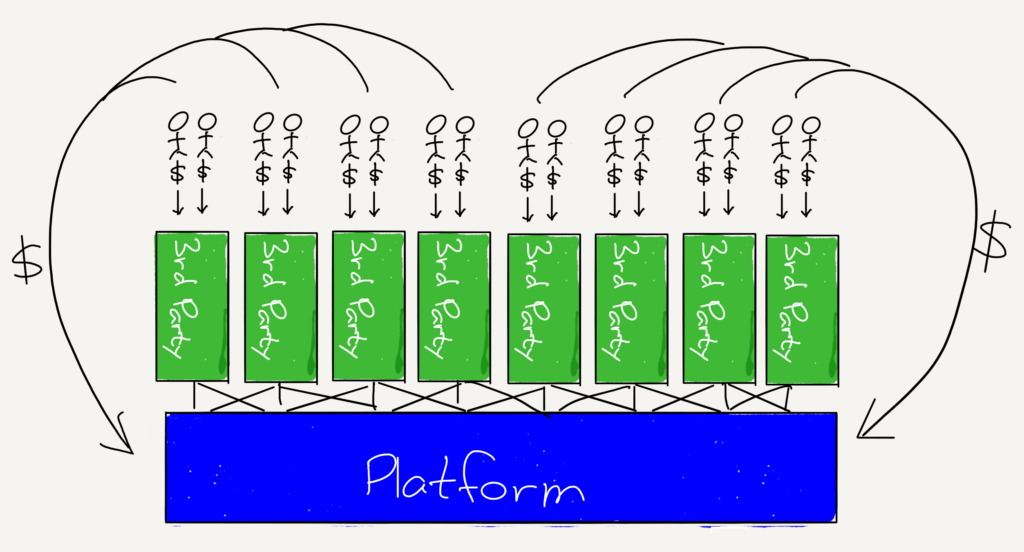

By this measure Windows was indeed the ultimate platform — the company used to brag about only capturing a minority of the total value of the Windows ecosystem — and the operating system’s clear successors are Amazon Web Services and Microsoft’s own Azure Cloud Services. In all three cases there are strong and durable businesses to be built on top.

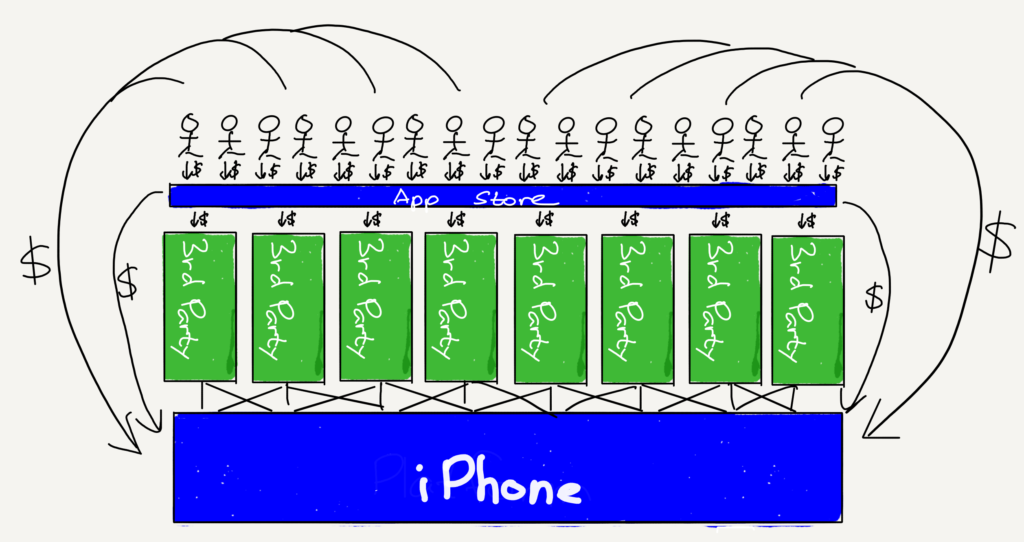

Once a platform dips under the Bill Gates Line, though, the long-term potential of a business built on a “platform” starts to decline. Apple’s App Store, for example, has all of the trappings of a platform, but Apple quite clearly captures the vast majority of the overall ecosystem, both because of the profitability of the iPhone and also because of its control of App Store economics; the paucity of strong and durable businesses on the App Store is a natural outgrowth of that.

Note that Apple’s ability to control the economics of its developers comes from intermediating the relationship of those developers with customers.

Aggregators, Not Platforms

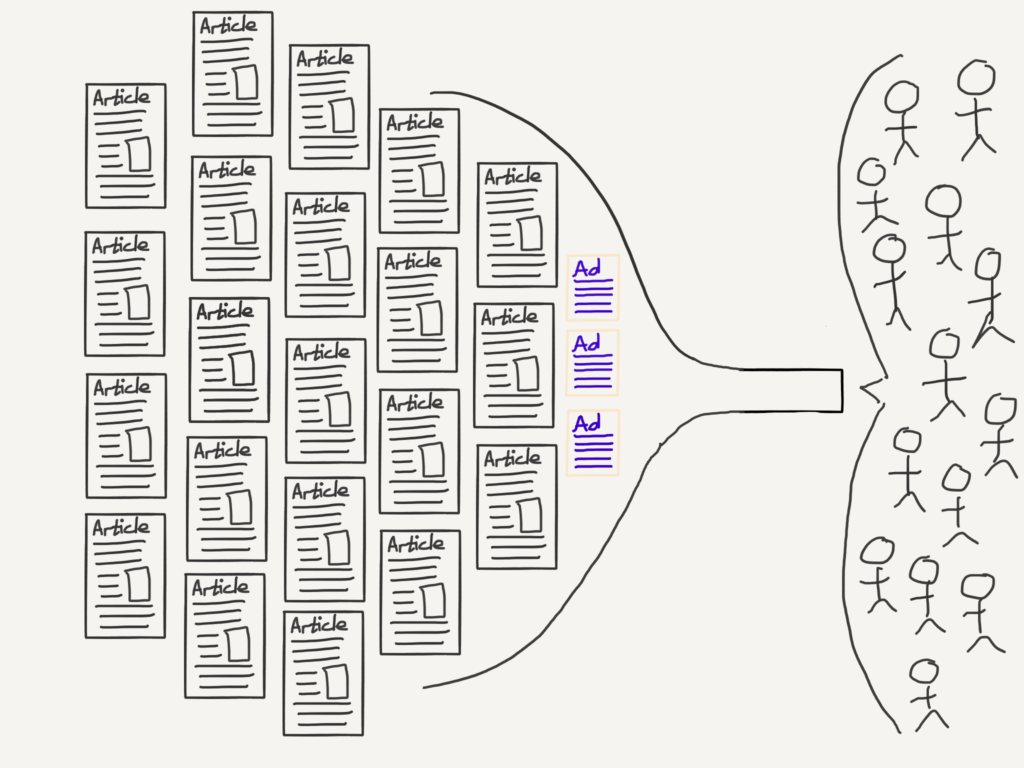

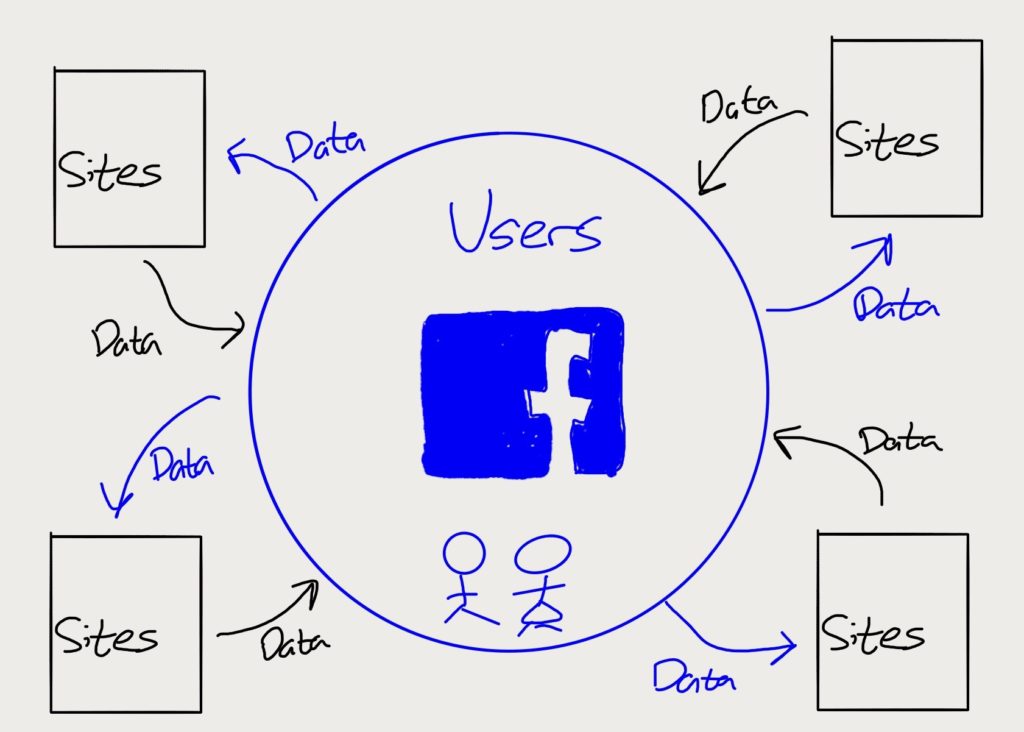

Facebook and Google take this intermediation to the extreme, leveraging their ability to drive discovery of the sheer abundance of information on their network and the Internet broadly:

It follows that Facebook and Google’s “platforms” not only don’t meet the Bill Gates Line, they don’t even register on the graph: they are the purest expression of aggregators. From my original formulation:

The fundamental disruption of the Internet has been to turn this dynamic on its head. First, the Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale.

This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be aggregated at scale leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

The result is the shift in value predicted by the Conservation of Attractive Profits. Previous incumbents, such as newspapers, book publishers, networks, taxi companies, and hoteliers, all of whom integrated backwards, lose value in favor of aggregators who aggregate modularized suppliers — which they often don’t pay for — to consumers/users with whom they have an exclusive relationship at scale.

This is ultimately the most important distinction between platforms and aggregators: platforms are powerful because they facilitate a relationship between 3rd-party suppliers and end users; aggregators, on the other hand, intermediate and control it.

Moreover, at least in the case of Facebook and Google, the point of integration in their respective value chains is the network effect. This is what I was trying to get at last week in The Moat Map with my discussion of the internalization of network effects:

- Google has had the luxury of operating in an environment — the world wide web — that was by default completely open. That let the best technology win, and that win was augmented by the data that comes from serving an ever-increasing portion of the market. The end result was the integration of end users and the data feedback cycle that made Google search better and better the more it was used.

- Facebook’s differentiator, meanwhile, is the relationships between friends and family; the company has subsequently integrated that network effect with consumer attention, forcing all of the content providers to jostle for space in the Newsfeed as pure commodities.

It’s worth noting, by the way, why it was Facebook could come to be a rival to Google in the first place; specifically, Facebook had exclusive data — those relationships and all of the behavior on Facebook’s site that resulted — that Google couldn’t get to. In other words, Facebook succeeded not by being a part of Google, but by being completely separate.

Succeeding in a World of Aggregators

This gets at why I find Yelp’s complaints a bit besides the point: the company seems to be expending an awful lot of energy to regain the right to give Google the content Yelp worked hard to acquire. There is revenue there, of course, just as there is in the production of commodities generally, but without a sustainable cost advantage it’s not the best route to building a strong and durable business.

Of course that is the bigger problem: I noted above that Google’s library of ratings and reviews has grown substantially over the past few years; users generating content are the ultimate low-cost supplier, and losing that supply to Google is arguably a bigger problem for Yelp than whatever advertising revenue it can wring out from people that would click through on a hypothetical Google Answer Box that used 3rd-party sources. And, it should be noted, that Yelp’s entire business is user-generated reviews: they and similar vertical sites are likely to do a far better job of generating, organizing, and curating such data.

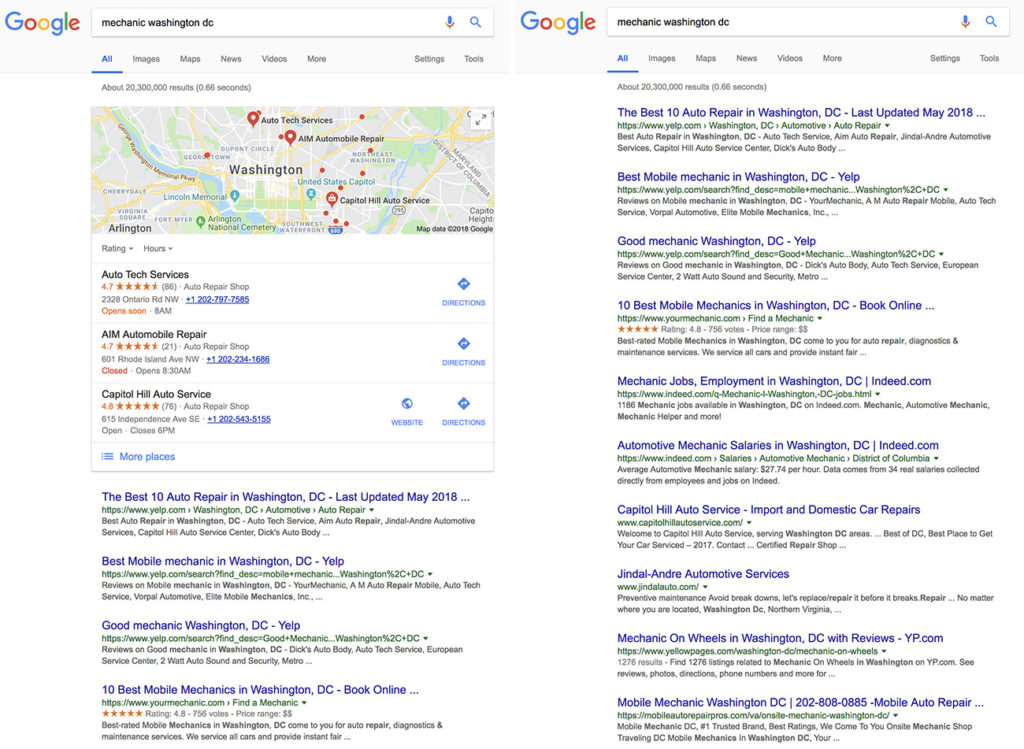

Still, I can’t help but wonder whether or not Yelp’s problem is not that Google is using its own content in the Answer Box, but rather the Answer Box itself; which of these set of results would be better for Yelp’s business, even in a hypothetical world where Answer Box content comes from Yelp?

Presuming that the answer is the image on the right — driving users to Yelp is both better for the bottom line and better for content generation, which mostly happens on the desktop — and it becomes clear that Yelp’s biggest problem is that the more useful Google is — even if it only ever uses Yelp’s data! — the less viable Yelp’s business becomes. This is exactly what you would expect in an aggregator-dominated value chain: aggregators completely disintermediate suppliers and reduce them to commodities.

To that end, this is why the best strategies entail business models that avoid Google and Facebook completely: look no further than Amazon, which last month stopped buying Google Shopping ads, something the company can afford to do given that half of shoppers start their product searches on Amazon. To be sure, Amazon is plenty powerful in its own right, but it is a hard-to-ignore example of Google’s favorite argument that “competition is only a click away.”

Yelp Versus Google

Still, I have sympathy for Yelp’s position; Stoppelman told 60 Minutes:

If I were starting out today, I would have no shot of building Yelp. That opportunity has been closed off by Google and their approach…because if you provide great content in one of these categories that is lucrative to Google, and seen as potentially threatening, they will snuff you out.

Stoppelman is right, but the reason is perhaps less nefarious than it seems; the 60 Minutes report explained why in the voiceover:

Yelp and countless other sites depend on Google to bring them web traffic — eyeballs for their advertisers.

Yelp, like many other review sites, has deep roots in SEO — search-engine optimization. Their entire business was long predicated on Google doing their customer acquisition for them. To the company’s credit it has become a well-known brand in its own right, and now gets around 70% of its visits via its mobile app. Those visits are very much in the Amazon model I highlighted above: users are going straight to Yelp and bypassing Google directly.

That, though, isn’t great for Google! It seems a bit rich that Yelp should be free to leverage its app to avoid Google completely, and yet demand that Google continue to feature Yelp prominently in its search results, particularly on mobile, where the Answer Box has particular utility. I get that Yelp feels like Google has changed the terms of the deal from when Yelp was founded in 2004, but the reality is that the change that truly mattered was mobile.

What I do find compelling is a new video that Yelp put out yesterday; while it makes many of the same points as the one above, instead of being focused on regulators it is targeting Google itself, arguing that Google isn’t living up to its own standards by not featuring the best results, and not driving traffic back to sites that make the content Google needs (by, for example, not including prominent links to the content filling its answer boxes; Yelp isn’t asking that they go away, just that they drive traffic to 3rd parties). Google may be an aggregator, but it still needs supply, which means it needs a sustainable open web. The company should listen.

Facebook and Data Portability

Facebook, unfortunately for its suppliers, faces no such constraints: the content that is truly differentiated is made by Facebook’s users, and it is wholly owned by Facebook. Facebook is even further from the Bill Gates Line than Google is: the latter at least needs commoditized suppliers; the former can take or leave them on a whim, and does.

That is why I’ve come to realize a popular prescription for Facebook’s dominance, data portability, put forward this week by a coalition of progressive organizations under the umbrella Freedom From Facebook, is so mistaken.3 The problem with data portability is that it goes both ways: if you can take your data out of Facebook to other applications, you can do the same thing in the other direction. The question, then, is which entity is likely to have the greater center of gravity with regards to data: Facebook, with its social network, or practically anything else?

Remember the conditions that led to Facebook’s rise in the first place: the company was able to circumvent Google, go directly to users, and build a walled garden of data that the search company couldn’t touch. Partnering or interoperating with companies below the Bill Gates Line, particularly aggregators, is simply an invitation to be intermediated. To demand that governments enforce exactly that would be a mistake that only helps Facebook.4

The broader takeaway is that distinguishing between platforms and aggregators isn’t simply an academic exercise: it should affect how companies think about their competitive environment vis-à-vis the biggest companies in tech, and, just as importantly, it should weigh heavily on regulators. The Microsoft antitrust battles of the 2000s were in many respects about enforcing interoperability as a way of breaking into the Microsoft platform; today antitrust should be far more concerned about aggregators capturing everything they touch by virtue of their control of end users.

That’s the thing about the “Generals fight the last war” saying; itas usually applied to the losing side that made mistake after mistake while the victors leveraged the new world order.

- I’ve discussed why I disagree with Gary Reback’s views on monopoly and innovation in this Daily Update [↩︎]

- With regard to that FTC decision, yes, as the Wall Street Journal reported, some FTC staff members recommended suing Google; what is not true is that the recommendation was unanimous, or that FTC commissioners ultimately deciding to go in another direction was unusual. In fact, other staff groups in other groups recommended against the suit, and the decision of the FTC commissioners was unanimous. Again, that is not to say it was the right decision, but that the popular conception — including what was reported in that 60 Minutes piece — is a bit off [↩︎]

- To be fair, I’ve made the same argument previously, but I’ve changed my mind [↩︎]

- The group’s demand that Facebook be forced to divest Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger makes much more sense in terms of this framework (with the exception of Messenger, which has always been a part of Facebook). I strongly believe that the single best antitrust remedy for aggregators is limiting acquisitions [↩︎]