index.md 26KB

title: post-modern late-capitalism or late-capitalist post-modernism?

url: https://www.aaronland.info/weblog/2019/04/08/post/#mw19

hash_url: 13d7a83861

These are the slides and notes for a talk I gave at the 2019 Museums and the Web conference, in Boston. The talk accompanied a paper I wrote for the conference titled Mapping Space, Time, and the Collection at SFO Museum which documents the work we've been doing on the Mills Field website at SFO Museum.

Although the talk focuses on the work we're doing at SFO it is the continuation of some broader themes I've been actively banging on for a while. If you'd like to read more then I would point you to the still life with emotional contagion and this is my brick / there are many like it but this one is mine talks, both from 2014, the history is time breaking up with itself talk from 2015 and the fault lines — a cultural heritage of misaligned expectations talk from 2017.

In 2019, this is what I said.

Hi, my name is Aaron.

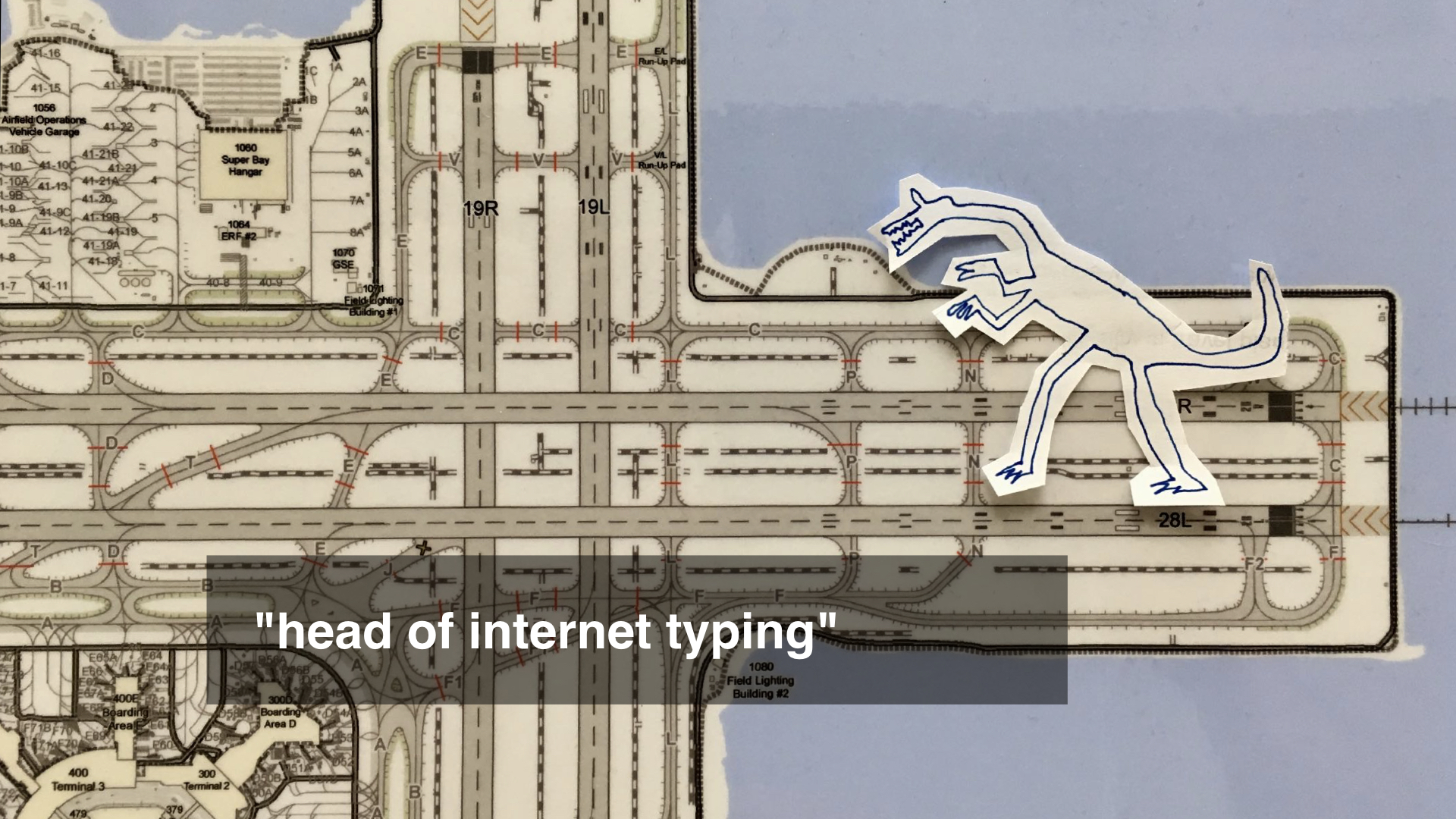

I am the Head of Internet Typing at the San Francisco International Airport Museum. As silly as a title like that may sound (and I actually have an even more vague and opaque official title for HR purposes) it is the best way to describe my role at the museum.

In the past I have been part of the teams at Flickr, Stamen Design and Mapzen where the common thread has been maps and location. I was also part of the Digital and Emerging Media team at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum helping to re-open the museum and launch the Pen in 2014.

The San Francisco International Airport, or SFO, first opened in 1927 on the site of the old Mills Field in San Mateo County. Although SFO is physically situated in San Mateo it is owned and operated by the City and County of San Francisco. Like the Farallon Islands, 30 miles off the Pacific Coast, SFO is actually part of San Francisco proper but unlike the Farallons is never shown that way on a map.

SFO is the 20th busiest airport in the world and 7th busiest in the United States. Last year, approximately 58 million passengers flew in and out of the airport.

Since 1980 the airport has had a museum. First accredited in 1999 the museum currently has 37 full-time and up to 24 part-time staff.

This is a photograph of the "Reflections in Wood - Surfboards and Shapers" exhibition currently on display in the International Terminal. Everything you see in this photo – from the curatorial programming, to registration and conservation, handling, exhibition design, fabrication and installation as well as the graphic design and photography – all of this was done in-house.

This is the work of my peers and they do this 30 to 40 times a year, 80 if you include the recently inaugurated video arts program. I just sit in the corner pecking away at a keyboard connected to the internet.

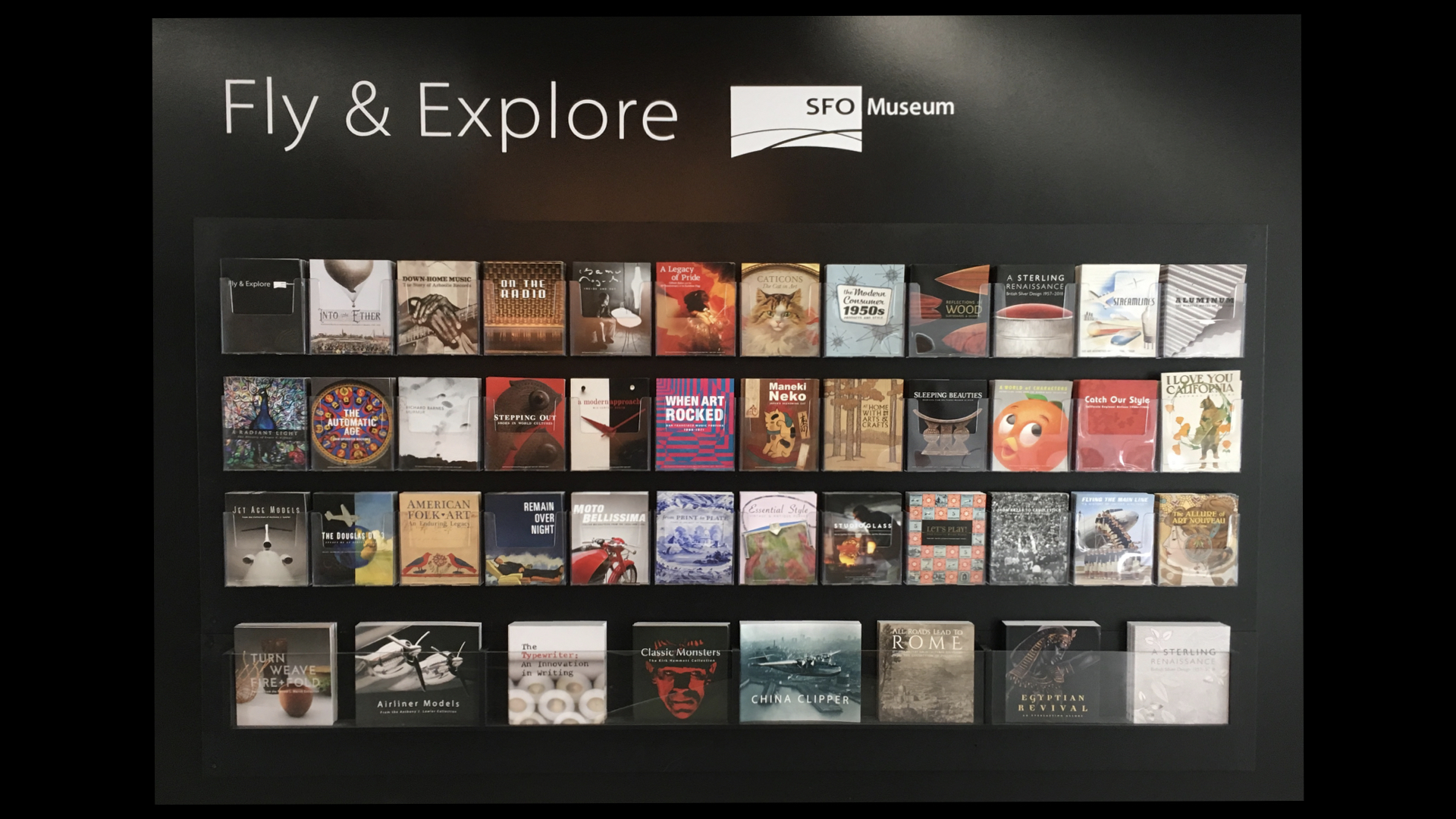

In addition to the almost 1,400 exhibitions the museum has produced since 1980 it has a permanent collection of 130,000 objects related to the history of the airport and commercial aviation. We also maintain a library and an archive of materials related to the aviation collection.

At any given moment there are upwards of 1,000 objects on display in the terminals.

On top of all of that we are charged with the care of the one hundred plus public artworks purchased by the San Francisco Arts Commission and installed on the airport property.

You might be wondering: How did all of this happen?

The answer is basically that in the 1970s the airport

commissioners decided SFO should be a nice place

to

visit. The Bay Area, and San Francisco in particular, is

complicated and has gotten a lot of things wrong over the

years. Sometimes though, when it cuts loose and gets it right

you end up with a museum in an airport.

If you measure things by foot traffic we are one of the busiest museums in the world. If that is the case we are also one of the busiest museums in the world that no one knows about. Nothing in modern life really prepares you for the idea that a museum should be part of an airport. San Francisco, as I've mentioned, is funny that way.

People often ask: Where is the museum? Almost no one is aware that there are over twenty gallery spaces spanning the terminals, both before and after security. Over the years there have been three times that number, rotating in and out as the airport has grown and changed.

So, in a very real sense the airport is the museum.

If people are ill-equipped to deal with the idea of a museum in an airport they are even less prepared to consider the idea that one has been there for the last 39 years. Lots of people will tell you about one or two exhibitions they've seen in a particular terminal but rarely have any idea of all the things that have come before it in that very same spot.

That's where the work I do comes in to the picture.

What is the promise of the internet – and in particular the web – if not the stringing together of all the things that came before or that follow any given moment?

When people ask me what I am doing I tell them it is to

ensure that every aspect of a trip to SFO, and every facet of

someone’s time spent in the airport, leads back to the museum’s

collection

and that we are using the internet to make that

possible.

That means the terminal you're standing in or the boarding gate you're waiting at, the airline or aircraft you're flying on, the places you're traveling to, the gallery space you're looking at or the places the objects in an exhibition are from. All of it. And all of it holds hands in some way with our collection.

By the way this is not how I see my role in relation to the airport or the museum. This is a mock-up I made to suggest installing the dinosaur that used to be on display in the old Terminal 2 out on the airfield. It's unlikely to ever happen but it's a nice idea, right?

I have also written a 5,000 word paper about that work for this conference and I don't want to spend my time with you today parroting everything I've already said there.

I want to do a high-level overview of the what and how discussed in detail in the paper so that we can spend a little more time on the why.

And then a little more time still on how I see our work in the context of some larger sector-wide dynamics that I believe we all need to address.

To explain what we're doing I need to begin with some basic statements of truth in our world:

That the notion of place is inseparable from an airport. After all everyone passing through our doors is coming from or going to some place.

Like the passengers everything the museum displays in its gallery cases is also from some place.

Part of SFO Museum's mandate is the history of the airport.

History is inseparable from place.

With that in mind we have made place and time (history) the joints – really a kind of double-joint – around which everything in the collection pivots. Everything means individual objects all the way up through the terminals and the airport itself and then beyond SFO to the other airports, cities and countries that are relevant to our collection. Then we multiply it all by time allowing any event – an exhibition, say – to be situated in a context relevant to that moment.

SFO in 1982, for example, was a very different place than it is today in 2019.

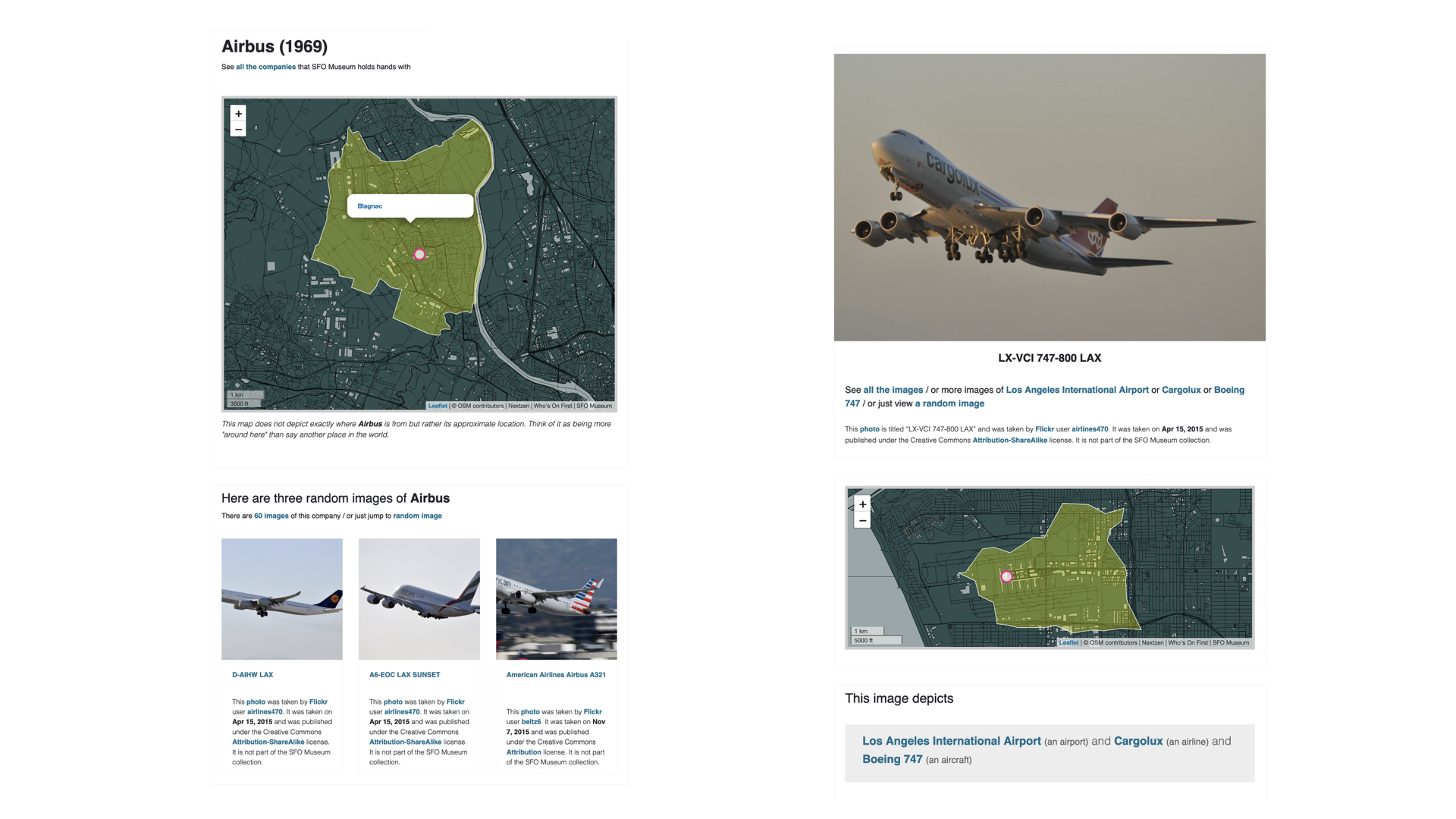

For those places outside the airport campus we are using an existing openly licensed gazetteer of places called Who's On First for record identifiers. This is our shared vocabulary for place.

For those places inside the airport we are extending the Who's On First model to represent the buildings and interior spaces over the years.

For example there are multiple records for "Terminal 1", each representing a unique phase-shift in its history. A phase-shift is defined as any meaningful change in how a passenger might experience that place. For example, the experience and the meaning of "Terminal 1" will change once more this summer with the opening of a new and much larger terminal named after Harvey Milk.

Each instance of Terminal 1 is linked to the record that precedes it and the record that follows it. We model any and all the architectural elements in our collection this way creating a tapestry of breadcrumbs that spans both place and history.

We are extending this approach to galleries and exhibitions as well as things in our collection that don't have ground truth; they aren't physical places you can visit. This includes objects and constituents, airlines and aircraft, historical flight data as well as photographs of things directly and indirectly related to the collection.

This is ongoing work and we may still paint ourselves in to a few corners but we think it is a promising approach.

I have always seen the Cooper Hewitt's search-by-colour functionality as a deliberate attempt to manufacture avenues in to their collection for people who do not already have an intimate knowledge of the decorative arts. We are trying to do the same thing, but with space and time, for our collection.

We are building for the web first, rather than targeting any of the big platform vendors.

The web embodies principles of openness and portability and access that best align with the needs, and frankly the purpose, of the cultural heritage sector.

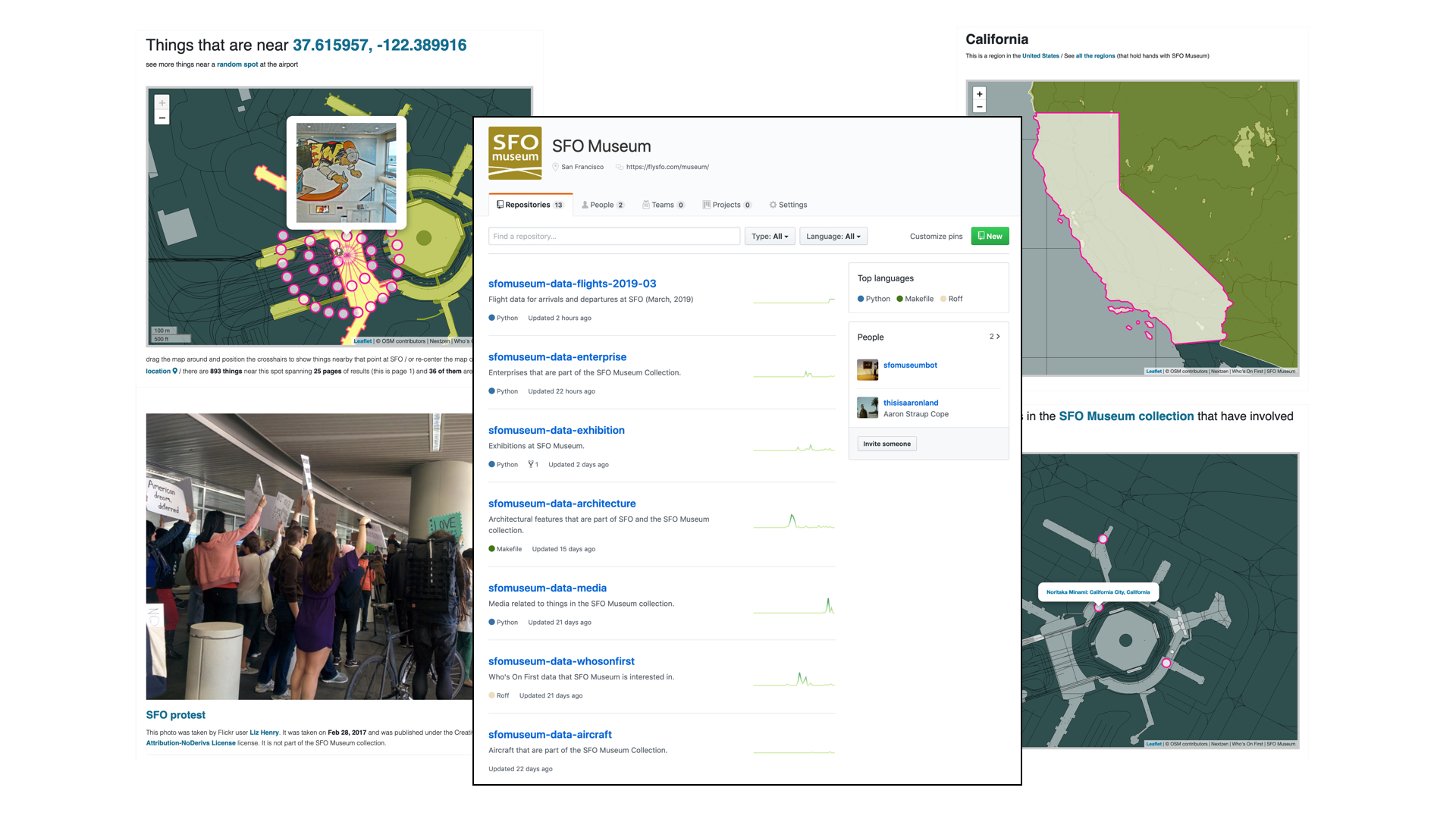

We are also publishing everything as openly-licensed data. We have chosen to publish everything using the GeoJSON format because it has a near-zero barrier to entry, is flexible enough to accommodate museum-specific metadata and because it is supported by nearly every geospatial application, open and closed source, on the market today. Everything we publish has location baked in to it from the start.

There is one other important twist in the way we are publishing open data.

Historically the model for most digital or web-based initiatives has been to first export data from an internal collections management system. Second, that data is massaged in to an intermediate form for use by the project at hand and then third, exported again in to a typically bespoke machine-readable format.

We have changed the order of things to publish the open data representation first and then, from there, to build our own websites and services on top of that.

Everything I've described so far has been built using the same raw materials that we've made available for you to do something with. This introduces a non-zero cost in the build process for the public-facing museum efforts but we believe it's worth the cost.

But why, right?

First of all we want other people to build new interfaces and new services, new "experiences" even, on top of our collection so this is a way to keep ourselves honest. If we can't build something with this stuff why should we imagine you will?

Second, we want to ensure that the data we release and the manner in which it is published, is actually robust and flexible enough to engender a variety of interfaces and uses because we need that variety. It is important to the museum because I don't believe there is, or should be, only one master narrative in to the collection.

To some degree all museums have reluctant audiences. Our visitors will not, and do not, warm up to our collections in the same way or at the same pace. This is especially true in an airport where people don't expect to find a museum in the first place and where our audience doesn't fit neatly in to a handful of demographic boxes.

As such we have an incentive to ensure that our work affords us the ability to iterate and experiment with as wide a range of interfaces and applications as possible, and for them to be just as fast and cheap to produce as they are to sustain over long periods of time and left to grow roots, to be nurtured.

We need to put in place an infrastructure that allows us to manage the cost of failure and germination, equally. A common mistake we make with digital initiatives in the cultural heritage sector is to assume those are same thing. They are not.

We need to start designing around the idea of false starts.

There is another, more practical, reason to design for false starts:

In 2019, if the past is any guide, most if not all the digital initiatives we work on today are destined to fail. More likely, they will just be left to die on the vine. Go ahead and take a moment to admire this beautiful chair while you let that sink in.

This is the elephant in the room, in every room where we talk about this stuff. It is a complex and nuanced subject, not one we have time to discuss properly here but it's real. My own feeling is that at its root it boils down to the problem of long-term staffing that permeates the sector – of hiring and more importantly keeping people with the requisite skills around.

Saying that, though, also a bit like being in the middle of a hurricane and complaining about the problem of hurricanes. Right now, the immediate problem is just getting through to the other side of the storm.

Right now the problem is thinking about how to build things to survive the short-term enthusiasms and trigger-finger disillusionments that seem to define our efforts. To prevent a reset to zero with each and every false start.

At this point, and based on some conversations I had during the conference, it's probably worth being explicit about a couple things in a way that I wasn't during the talk.

First, saying that we need to manage the cost of

failure

or design for false starts

should not be

confused with the maxim of failing fast (and failing

often)

. This has been rightly called out as a kind of intellectual dodge to accommodate and

legitimize lazy and sloppy practices that don't consider or

actively ignore their consequences. So, not that.

At the same time the worst possible outcome for the museum sector would be to use that critique as an excuse to continue with its own problematic working practices that have favoured overpriced aspirational battleships whose worth, whose success and failure, is measured only in third-party validation.

There is a way to work fast and cheap and do things the

right way, all while being forgiving of honest mistakes along

the way. It's hard work to juggle all those concerns but

that is not the same as impossible

. Sometimes failure really

is the manifestation of negligence but just as often it is the

guide rail we use to understand the shape of success.

Second, to say that everything we do today will fail

is not meant suggest we should just kick back, give up, get

our zen on and go to the bar. Not at all. It's pretty awful

watching what has happened to all the good work produced over

the years. It's wrong. It's wrong but it still happens and for

those reasons we need to be clear-eyed about what's going on

in order that we might figure out how to stop it from happening

again and again and again...

But why, indeed?

Let's take it for granted that a core function – again, a purpose – of the cultural heritage sector is access. From there let's imagine that access can be defined along an axis spanning broadcast to recall.

Broadcast being the ability to have your contemporary efforts reach as many people as possible with the least amount of friction. Recall being the ability for those same people to access all that broadcast material after the fact when you have moved on to some other contemporary concern.

The internet, it's clear, has been a boon to both but if we focus solely on broadcasting, on the "Channels" and on experiences in the moment then we are presented with something of an existential problem because the humanities are predicated on the idea of revisiting a subject or an idea and on revisiting it repeatedly.

The past keeps changing,

the historian Margaret

MacMillan has said, because we keep asking different questions

of it.

Put bluntly: Without recall there is little to revisit and if there is no revisiting is there even a cultural history?

The internet, and specifically the web, has made recall and

by extension access possible in a way that we have genuinely

never known before. In 2019 the web is not sexy

anymore

and compared to native platforms it can sometimes seems

lacking, but I think that speaks as much to people's desire for

something new

as it does to any apples to apples comparison. On measure – and that's the important part: on measure

– the web affords a better and more sustainable framework for

the cultural heritage to work in than any of the shifting agendas of

the various platform vendors.

For many years I think we all saw Tim Berners Lee's decision

to make the web open by design as quaint, the actions of a

nice scholarly British

man

. In recent years, as the platform vendors (sometimes called the

Stacks

) continue to build higher and higher walls in to

and out of their walled gardens, the magnitude of

Berners Lee's choice has become clearer and ever more important.

This is why we have chosen to do things in the ways I have described to you today.

In closing I'd like to leave you with a passage from the opening of Emily Wilson's translation of Homer's The Odyssey:

Tell the old story for our modern times Find the beginning