For the past few years, we have seen a lot of discussions around the concept of the Software Supply Chain. These discussions started around the time of LeftPad and escalated with multiple incidents in the past few years. The problem of all the work in this domain is that it forgets a fundamental point.

Before we get there, I am going to define what is usually meant by Supply Chain and suppliers, why we are applying to software. And then why attempts at bringing FOSS under that definition are deeply misguided.

In the past couple of decade, we have seen the rise of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). In particular, this has enabled a massive growth of the reuse of pieces of codes, packaged as libraries. This has been possible due to a massive ecosystem of infrastructure that bloomed around that idea. Package Managers exist for every programming language environment under the sun nowadays, with central repositories holding the metadata needed to find the libraries and handle their distributions.

This has been possible due to the FOSS Licences being pretty lenient, enabling a reuse and remix of these libraries without the massive legal and financial headache that would come otherwise. A modern software project will probably have hundreds if not thousands of these dependencies, from OpenSSL to a test framework or a datepicker, across a wide spectrum covering things like a JSON encoder/decoder library or even the libc of the OS it is deployed on.

This ecosystem of dependencies, a lot of them transitive (dependencies of a dependency), is what the Software Supply Chain model calls the Supply Chain of the project. Inside this model we will find tools that help manage it, like a Software Bill Of Materials (SBOM) that is supposed to hold the information of what libraries are used for this project, where they were found, which version, some hash of the content, etc.

The idea of a Supply Chain does not come out of nowhere of course. In the manufacturing industry, the supply chain is the long chain of suppliers needed to produce a particular factory’s output. As an example, if you assemble cars, you need seats, a lot of screws, cables, electronics, all kinds of stamped metal sheets, … Your cable supplier needs copper, plastic, energy and probably all kinds of machine tools. Machine tools that probably need other machine tools to be built, screws, bolts, nuts, some electronics too… And we can keep going through this long game of “what do you need to produce this car” until your diagram looks like a massive spaghetti ball.

And then someone in an unknown small factory in Germany gets sick and it happens that five levels higher in the chain everyone depends on their particular bolt, and we are all screwed. A version of this problem happened early in the work to deliver the vaccine for the Covid19, when supply chain specialists realised they would need a lot more glass vials than could be produced in a year worldwide.

In order to avoid this kind of snag five levels deep in the chain that would end up stopping their valuable production, manufacturing companies have spent a lot of effort over the years to build relationships with their suppliers, at every level of the process. It is both a really deep relationship and usually never enough, but isn’t that the case of every complex system?

Well because companies keep discovering that they have big problems in their products, and that it does not come from the code their software engineers wrote. The problem can come from the owner of a library deciding to stop providing access to it (Leftpad for example) and breaking half the Internet.

Or it could come from a massive library used for mundane digital infrastructure (Like OpenSSL or Log4J) discovering they have massive security problems that make half the Internet easy to pwn.

Or someone could talk to the people owning these libraries, convince them they are here to help, get access and add a crypto mining code to it for their own profit (so many cases that I do not know where to start).

Or the owner of the code could decide that he does not like people supporting a warmongering regime, so he will add code that destroys the computer of the engineers using his code, if they live in this part of the world (yes there have been a few instances of this too).

And then, everyone in these companies discover that their product is open to spooky “action at a distance” from code they did not know about. So the concept of “Software Supply Chain” comes in, to define all the things that need to be done by the people in the supply chain, the owners of these libraries, in order to be good citizens that do not break companies using the code downstream.

These rules govern things like how we test the code, how we protect who has access to it, how we release versions, how we validate its safety, how we organise work on the code, how we protect our personal accounts that control the code, etc

There is a small problem here. We are not suppliers. All the people writing and maintaining these projects, we are not suppliers. We do not have a business relationship with all these organisations. We are volunteers, writing code and putting it online under these Licences. And yes, we put it online for people to use them. But we do not get anything from it.

Hell even worse, a lot of the libraries that underpin the fabric of what we all call the digital economy have trouble getting enough money to pay for food. On this topic, I strongly advise everyone to take the time to read Nadia Eghbal Road and Bridges report to realize the depth of the problem. It is a bit old, as it was written in the aftermath of HeartBleed, but it is as relevant today as it was at the time.

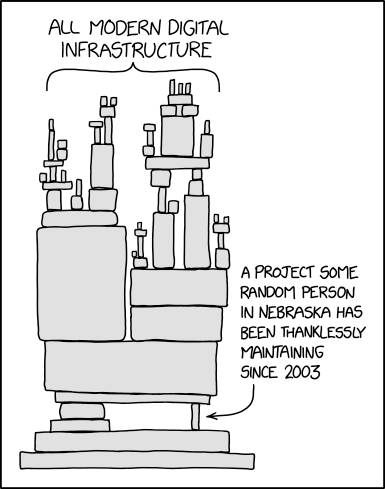

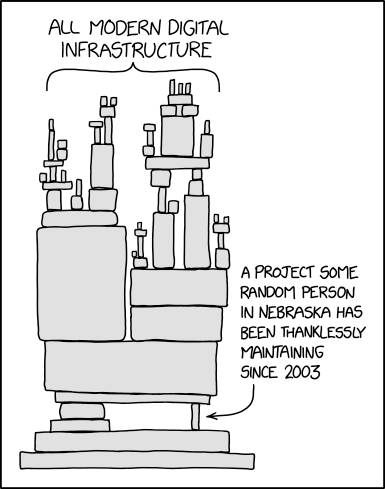

Or for a funnier, more visual explanation, XKCD 2347

And we know it. This is why in every single one of these licences, that govern the rules to reuse the work we put online in these libraries, you will find this paragraph, copied verbatim.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

It may feel a bit legalese, and yes, it shouts at you, but I can summarise it pretty easily. If you use this, I owe you nothing. At all. We have no relationship. I put this up online on the condition that if you use it, all the risks are on you.

What it means is that there is no supply chain here. Because there is no supplier. I am not providing you something that you bought from me. There is no relationship. I put something online because I wanted to. The fact you made your product depend on it is your responsibility. Not mine. Not the one of the providers. We provide libraries. We do not supply them. You cannot apply rules to me.

And quite honestly, I am not going to accept them. I barely have time to spend on doing the work on the FOSS libraries I maintain and doing so regularly burns out the people doing it.

Now, I am more than happy to become a supplier. You want me to work a certain way, I am more than happy to do it. But to do that, I am going to have to become a supplier. Which means you are going to have to start to pay me. A fair price, that we can negotiate. Under a different licence.

Until then, I am not your supplier. So all your Software Supply Chain ideas? You are not buying from a supplier, you are a raccoon digging through dumpsters for free code. So I would advise you to put these rules in the same dumpster. And remember. I am not a supplier. Because

THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”