Source originale du contenu

Usually the first thing you do when you have an idea for a product or company is to register the domain. Because the web came before social networks and mobile, the conventional wisdom is that you need a website to serve as the canonical destination for whatever you’re peddling. The website is head of the beast, so to speak.

This is still true in spite of the decline of the web, the poor aesthetics of URL’s, the existence of App Store pages that are more important for conversion purposes than your website, the primacy of social, the astronomical rise of messaging, and the death of the homepage.

The homepage. It sounds so quaint now, doesn’t it? If you’re a media outlet launching today, is your "homepage" even a top priority? If a majority of traffic is coming from referrals on social networks, such that the majority of your visitors are arriving and then departing from singular links, in what sense is your homepage really your home?

On today’s internet, there is no home. You probably have a website, but you might also have two to four apps (iOS, Android, and then phone and tablet), and accounts on Facebook (and Messenger), Twitter, Snapchat, Pinterest and Instagram). And the Internet is now so big and so fragmented that you could easily build a business on one platform while ignoring the rest. Instagram initially proved that by going mobile app only and ignoring the web for years.

More recently, one new media venture has opted to forgo both the web and native mobile apps, instead publishing on Instagram only. The most profitable outfit in entertainment these days is a woman who only publishes YouTube videos. One new retail outfit is ignoring virtually all of the above and going SMS only. What might be the fastest-growing automotive social network in the world has 200K Facebook fans and 500K Instagram followers, yet their website traffic barely registers and have no App Store rankings to speak of. Buzzfeed has dedicated staff who create content that will never appear on any Buzzfeed owned property.

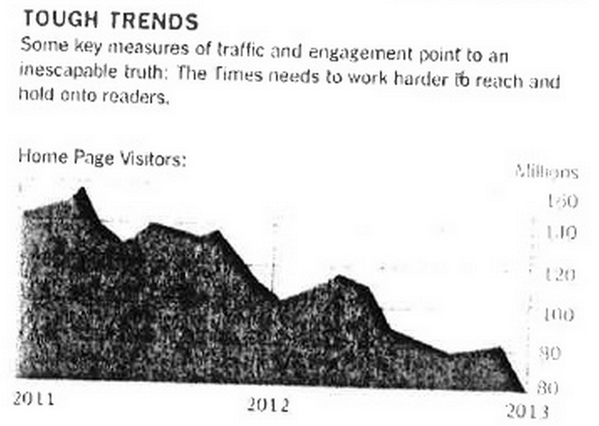

These companies are relatively new outfits, and all but Buzzfeed are still small. But what about big, established brands today? If you’re a media outlet like the New York Times, and attention is being sucked up by Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and Snapchat while your homepage has lost 50% of its traffic in two years, what do you do?

The New York Times lost half of its homepage visitors between 2011 and 2013. Source.

The New York Times lost half of its homepage visitors between 2011 and 2013. Source.

Do you sail into the wind and develop a bevy of web experiences and eight apps for iOS alone? How do you even compete as a Canonical Destination publisher when all the best tech minds are working for Facebook's of the world?

Or do you sail with the wind and start publishing directly to the social networks? This means that you’ve lost control of your destiny as a publisher, but is that such a bad thing? Consider that news organizations have historically been publishers because, pre-internet, how else were people going to read your stuff if you didn’t print and distribute it yourself? Meanwhile, the upshot of forgoing your role as publisher is that you’ve hopefully solidified your role as a content creator and curator. Maybe you exist and hopefully thrive as a decentralized brand which, when displayed as an avatar alongside your content, conveys a level of trust and gravitas that no other avatar can convey?

The evolution of media?

And what if you’re a retail brand like Banana Republic that doesn’t want to lose all internet shoppers to retailers that are internet natives? Do you stay the course with your poorly rated app, crusty email newsletters, your store on Amazon, and the hope that people will always be willing to type banana republic dot com into their mobile browser?

Or do you make make the same move as the New York Times and accept the networks’ bargain? That is, "You do what you do best—be it media or retail design and manufacturing—and we’ll do what we do best—publishing, distribution, and soon merchandising and retail."

Ben Thompson’s Smiling Curve of Publishing. Source.

That sounds like an odd deal for retailers but it’s identical to Amazon’s proposition. Think about it: If you wanted to buy a Banana Republic shirt, doesn’t the convenience of Amazon, or maybe soon Facebook Messenger, often trump navigating an unfamiliar BananaRepublic.com or Banana Republic app and then entering your credit card details anew?

While all of this seems dire if you’re a brand trying to maintain its independence, consider that "aitch tee tee pee colon backslash backslash double u double u double u dot banana republic dot com" probably didn’t seem so great for branding in the early days of the web, yet it soon came to represent as canonical a destination for the brand as the brick-and-mortar store. In the next few years, maybe the homepage diminishes in importance, and maybe it’s unfortunate that instead of having some canonical destination — be it a website, an app, or whatever—you’re now being foisted onto closed, proprietary silos like Facebook et al.

But maybe if you’ve got a strong brand, like The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Economist, Victoria Secret, American Apparel, or Lululemon, you’re well suited to thrive in an environment that the social networks foster so well: Identity, curation, and tastemaking. After all, that’s exactly what a brand is: A collection of ideas and feelings that travel with you even when the brand is not in sight, and come rushing to the fore as soon as the trademark comes into view.

You could look at it as a mere reorganization of namespacing. Whereas the homepage once conferred some sense of reaching your canonical destination, it’s now your name on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Amazon etc. that consumers are searching for. And so long as we have trademark law, owning your name and trademark might just be all you need to be everywhere and anywhere.

Additional Reading

The ideas in this post were rattling around my head until I read Tom Critchlow’s Decentralized Brands & The Future of Content Marketing. This post was largely inspired by his; so much so that I lifted all of his examples and sources.