Source originale du contenu

I spent over 25 hours building a cut-down version of Sapiens. The goal? Future-me should be happy to read this once future-me forgets how we evolved. It’s massive for a blog post, just under 30 minutes, but that’s the best I could do, condensing 9 hours worth of material.

I’ve tried to keep editing to a minimum: It’s the original text, edited to ensure it still flows like the book.

You can get the book here

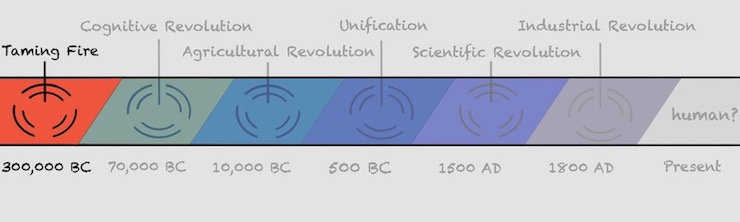

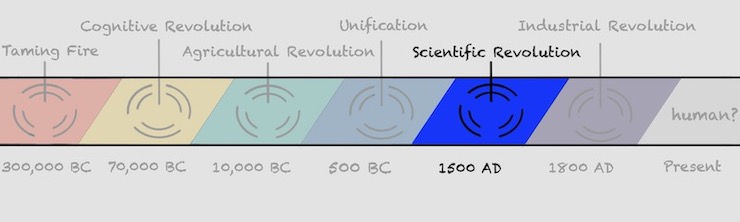

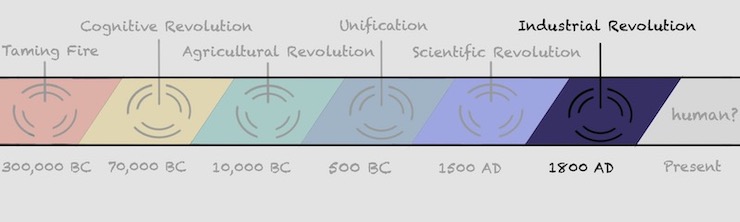

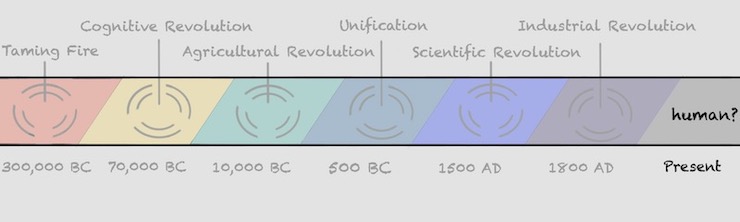

The best way of navigating is clicking on the images. These are best experienced on a tablet or a laptop. I’ve also included the table of contents, which work well on every screen size.

Development of brains

What caused our brains to develop? We’re not sure.

It doesn’t seem likely. A larger brain needs more energy and thus reduces the chance you’ll survive. Getting more energy meant hunting more.

One contributing factor was the domestication of fire. Fire paved the way for cooking.

Whereas chimpanzees spend 5 hours a day chewing raw food, a single hour suffices for people eating cooked food. The advent of cooking enabled humans to eat more kinds of food, to devote less time to eating, and to make do with smaller teeth and shorter intestines. Some scholars believe there is a direct link between the advent of cooking, the shortening of the human intestinal track, and the growth of the human brain. Since long intestines and large brains are both massive energy consumers, it’s hard to have both. By shortening the intestines and decreasing their energy consumption, cooking inadvertently opened the way to the jumbo brains.

And, we weren’t alone. Competing with us were the Neanderthals, among other species. They were stronger, they had bigger brains, and they could survive the cold. How come, then, did we “win”?

We aren’t sure. The most likely answer is the very thing that makes the debate possible: Homo sapiens conquered the world thanks above all to its unique language.

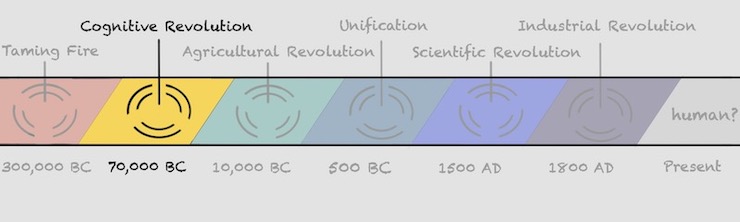

Cognitive Revolution

The appearance of new ways of thinking and communicating, between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago, constitutes the Cognitive Revolution. What caused it? We’re not sure. The most commonly believed theory argues that accidental genetic mutations changed the inner wiring of the brains of Sapiens, enabling them to think in unprecedented ways and to communicate using a new type of language. We might call it the Tree of Knowledge mutation.

What’s special about our language?

Our language is amazingly supple. We can connect a limited number of sounds and signs to produce an infinite number of sentences, each with a distinct meaning. We can thereby ingest, store and communicate a prodigious amount of information about the surrounding world. A monkey can yell to its comrades, ‘Careful! A lion!’ But a modern human can tell her friends that this morning, near the bend in the river, she saw a lion tracking a herd of bison. She can then describe the exact location, including the different paths leading to the area. With this information, the members of her band can put their heads together and discuss whether they ought to approach the river in order to chase away the lion and hunt the bison.

Yet the truly unique feature of our language is not its ability to transmit information about men and lions. Rather, it’s the ability to transmit information about things that do not exist at all. As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched or smelled.

Using language, lots of humans could work together, form a tribe, help each other, and hunt together.

However, communicating with lots of people brings with it new co-ordination problems. The critical threshold for a group interacting together is 150 people.

How did Homo sapiens manage to cross this critical threshold, eventually founding cities comprising tens of thousands of inhabitants and empires ruling hundreds of millions? The secret was probably the appearance of fiction. Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths. This is an imagined reality.

Unlike lying, an imagined reality is something that everyone believes in, and as long as this communal belief persists, the imagined reality exerts force in the world.

In other words, while the behaviour patterns of archaic humans remained fixed for tens of thousands of years, Sapiens could transform their social structures, the nature of their interpersonal relations, their economic activities and a host of other behaviours within a decade or two.

For example, consider trade. Trade cannot exist without trust, and it is very difficult to trust strangers. The global trade network of today is based on our trust in such fictional entities as the dollar, the Federal Reserve Bank, and the totemic trademarks of corporations. When two strangers in a tribal society want to trade, they will often establish trust by appealing to a common god, mythical ancestor or totem animal.

Our Tree of Knowledge mutation was significant. However, it’s not just our biology that brought us where we are today.

-

Biology sets the basic parameters for the behaviour and capacities of Homo sapiens. The whole of history takes place within the bounds of this biological arena.

-

This arena is extraordinarily large, allowing Sapiens to play an astounding variety of games. Thanks to their ability to invent fiction, Sapiens create more and more complex games, which each generation develops and elaborates even further

-

Consequently, in order to understand how Sapiens behave, we must describe the historical evolution of their actions.

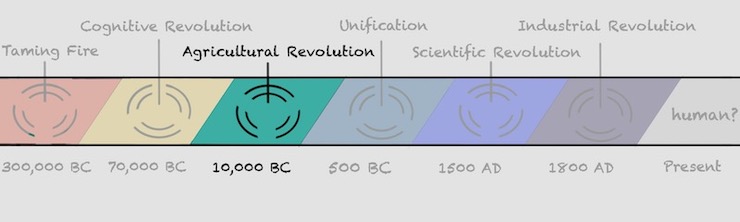

Agricultural Revolution

The currency of evolution is neither hunger nor pain, but rather copies of DNA helixes. Just as the economic success of a company is measured only by the number of dollars in its bank account, not by the happiness of its employees, so the evolutionary success of a species is measured by the number of copies of its DNA. If no more DNA copies remain, the species is extinct, just as a company without money is bankrupt. If a species boasts many DNA copies, it is a success, and the species flourishes. From such a perspective, 1,000 copies are always better than a hundred copies. This is the essence of the Agricultural Revolution: the ability to keep more people alive under worse conditions.

Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more difficult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud.

Compared to foraging, working a bit harder on the farm meant more food. Settling down on the farm also meant greater freedom to reproduce - you’re not travelling all the time, so you can afford to have more children. This in turn, meant a higher population. And a higher population meant higher food requirements. Thus, the farmers were forced to work even harder.

Why didn’t humans abandon farming when the plan backfired? Partly because it took generations for the small changes to accumulate and transform society and, by then, nobody remembered that they had ever lived differently. And partly because population growth burned humanity’s boats. If the adoption of ploughing increased a village’s population from a hundred to 110, which ten people would have volunteered to starve so that the others could go back to the good old times? There was no going back. The trap snapped shut.

One of history’s few iron laws is that luxuries tend to become necessities and spawn new obligations

This discrepancy between evolutionary success and individual suffering is perhaps the most important lesson we can draw from the Agricultural Revolution. When we study the narrative of plants such as wheat and maize, maybe the purely evolutionary perspective makes sense. Yet in the case of animals such as cattle, sheep and Sapiens, each with a complex world of sensations and emotions, we have to consider how evolutionary success translates into individual experience.

Imagined Realities - Solving the co-ordination problem

According to the science of biology, people were not ‘created’. They have evolved. And they certainly did not evolve to be ‘equal’. The idea of equality is inextricably intertwined with the idea of creation.

A natural order is a stable order. There is no chance that gravity will cease to function tomorrow, even if people stop believing in it. In contrast, an imagined order is always in danger of collapse, because it depends upon myths, and myths vanish once people stop believing in them. In order to safeguard an imagined order, continuous and strenuous efforts are imperative. Some of these efforts take the shape of violence and coercion.

To say that a social order is maintained by military force immediately raises the question: what maintains the military order? It is impossible to organise an army solely by coercion. At least some of the commanders and soldiers must truly believe in something, be it God, honour, motherland, manhood or money.

To maintain an imagined order, we need people who believe in it - the military, the elites, and the peasants.

Three main factors prevent people from realising that the order organising their lives exists only in their imagination:

The imagined order is embedded in the material world.

For example, houses have small rooms for every person living inside. This architecture promotes Individualism.

The imagined order shapes our desires.

Most people do not wish to accept that the order governing their lives is imaginary, but in fact every person is born into a pre-existing imagined order, and his or her desires are shaped from birth by its dominant myths. Our personal desires thereby become the imagined order’s most important defences.

The elite of ancient Egypt spent their fortunes building pyramids and having their corpses mummified, but none of them thought of going shopping in Babylon or taking a skiing holiday in Phoenicia. People today spend a great deal of money on holidays abroad because they are true believers in the myths of romantic consumerism. Romanticism tells us that in order to make the most of our human potential we must have as many different experiences as we can.

A wealthy man in ancient Egypt would never have dreamed of solving a relationship crisis by taking his wife on holiday to Babylon. Instead, he might have built for her the sumptuous tomb she had always wanted.

Few question the myths that cause us to desire the pyramid in the first place.

The imagined order is inter-subjective.

Even if by some superhuman effort I succeed in freeing my personal desires from the grip of the imagined order, I am just one person. In order to change the imagined order I must convince millions of strangers to cooperate with me. For the imagined order is not a subjective order existing in my own imagination – it is rather an inter-subjective order, existing in the shared imagination of thousands and millions of people.

The inter-subjective is something that exists within the communication network linking the subjective consciousness of many individuals. If a single individual changes his or her beliefs, or even dies, it is of little importance. However, if most individuals in the network die or change their beliefs, the inter-subjective phenomenon will mutate or disappear

A change of such magnitude can be accomplished only with the help of a complex organisation, such as a political party, an ideological movement, or a religious cult. However, in order to establish such complex organisations, it’s necessary to convince many strangers to cooperate with one another. And this will happen only if these strangers believe in some shared myths. It follows that in order to change an existing imagined order, we must first believe in an alternative imagined order.

Preserving the imagined reality

After the imagined order, comes a means of facilitating and propagating the order.

Between the years 3500 BC and 3000 BC, some unknown Sumerian geniuses invented a system for storing and processing information outside their brains, one that was custom-built to handle large amounts of mathematical data. The Sumerians thereby released their social order from the limitations of the human brain, opening the way for the appearance of cities, kingdoms and empires. The data-processing system invented by the Sumerians is called ‘writing’.

Animals that engage strangers in ritualised aggression do so largely by instinct – puppies throughout the world have the rules for rough-and-tumble play hard-wired into their genes. But human teenagers have no genes for football. They can nevertheless play the game with complete strangers because they have all learned an identical set of ideas about football. These ideas are entirely imaginary, but if everyone shares them, we can all play the game.

With greater numbers and growing imagined orders, we needed a system to organise the rules: No one person could remember all of them.

Just imprinting a document in clay is not enough to guarantee efficient, accurate and convenient data processing. That requires methods of organisation like catalogues, methods of reproduction like photocopy machines, methods of rapid and accurate retrieval like computer algorithms, and pedantic librarians who know how to use these tools. Inventing such methods proved to be far more difficult than inventing writing.

More individual suffering

Understanding human history in the millennia following the Agricultural Revolution boils down to a single question: how did humans organise themselves in mass-cooperation networks, when they lacked the biological instincts necessary to sustain such networks? The short answer is that humans created imagined orders and devised scripts. These two inventions filled the gaps left by our biological inheritance.

However, for many, this was a dubious blessing.

With an order came social and political hierarchies.

Throughout history, and in almost all societies, concepts of pollution and purity have played a leading role in enforcing social and political divisions and have been exploited by numerous ruling classes to maintain their privileges.

If you want to keep any human group isolated – women, Jews, Roma, gays, blacks – the best way to do it is convince everyone that these people are a source of pollution.

This led to a vicious circle of exploitation of people “lower” on the social ladder.

These Social structures form depending on what hierarchy is visible or convenient.

One example is the dark-skinned slaves.

European conquerors of America chose to import slaves from Africa rather than from Europe or East Asia due to three circumstantial factors.

Firstly, Africa was closer, so it was cheaper to import slaves from Senegal than from Vietnam.

Secondly, in Africa there already existed a well-developed slave trade (exporting slaves mainly to the Middle East), whereas in Europe slavery was very rare. It was obviously far easier to buy slaves in an existing market than to create a new one from scratch

Thirdly, and most importantly, American plantations in places such as Virginia, Haiti and Brazil were plagued by malaria and yellow fever, which had originated in Africa. Africans had acquired over the generations a partial genetic immunity to these diseases, whereas Europeans were totally defenseless and died in droves. It was consequently wiser for a plantation owner to invest his money in an African slave than in a European slave or indentured labourer

Paradoxically, genetic superiority (in terms of immunity) translated into social inferiority.

Different societies adopt different kinds of imagined hierarchies. Race is very important to modern Americans but was relatively insignificant to medieval Muslims. Caste was a matter of life and death in medieval India, whereas in modern Europe it is practically non-existent. One hierarchy, however, has been of supreme importance in all known human societies: the hierarchy of gender. People everywhere have divided themselves into men and women. And almost everywhere men have got the better deal, at least since the Agricultural Revolution.

How can we distinguish what is biologically determined from what people merely try to justify through biological myths? A good rule of thumb is ‘Biology enables, Culture forbids.’ Biology is willing to tolerate a very wide spectrum of possibilities. It’s culture that obliges people to realise some possibilities while forbidding others. Biology enables women to have children – some cultures oblige women to realise this possibility. Biology enables men to enjoy sex with one another – some cultures forbid them to realise this possibility.

Thus, the Agricultural Revolution led to much individual suffering. It led to more humans with a limited diet, higher risk of starvation, imagined realities to co-ordinate so many people, scripts to preserve that order, and social hierarchies to maintain that order. At the same time, it was an evolutionary success - much more people were alive at any given time.

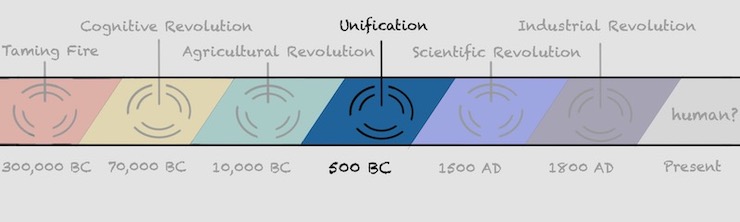

Unification of Humankind

All imagined orders created untill 1000 BC had a clear boundary. In united Egypt, everyone outside the country were barbarians. Our culture vs theirs. As Seth Godin puts it today, “People like us, do things like this.” - a microculture.

The first millennium BC witnessed the appearance of three potentially universal orders, whose devotees could for the first time imagine the entire world and the entire human race as a single unit governed by a single set of laws. Everyone was ‘us’, at least potentially. There was no longer ‘them’.

The first universal order to appear was economic: the monetary order.

The second universal order was political: the imperial order.

The third universal order was religious: the order of universal religions such as Buddhism, Christianity and Islam.

Money

The rise of cities and kingdoms and the improvement in transport infrastructure brought about new opportunities for specialisation. Densely populated cities provided full-time employment not just for professional shoemakers and doctors, but also for carpenters, priests, soldiers and lawyers.

Everyone always wants money. This is perhaps its most basic quality. Everyone always wants money because everyone else also always wants money, which means you can exchange money for whatever you want or need.

How Money Works

Money is a psychological construct. It works by converting matter into mind. But why does it succeed? Why should anyone be willing to exchange a fertile rice paddy for a handful of useless cowry shells? Why are you willing to flip hamburgers, sell health insurance or babysit three obnoxious brats when all you get for your exertions is a few pieces of coloured paper?

Its a system of mutual trust, and not just any system of mutual trust: money is the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised.

The first iteration of money were set weights made of pure silver. Everyone had to keep scales handy to measure them. Counterfeiting was easy. You couldn’t be sure it’s really pure silver.

Coins helped solve these problems. The mark imprinted on them testifies to their exact value, so the shoemaker doesn’t have to keep a scale on his cash register. More importantly, the mark on the coin is the signature of some political authority that guarantees the coin’s value.

With notes, we’ve extended the same basic concept. The Treasury guarantees the value of the notes, the number signifies its value.

Proliferation of gold

After silver, came gold. The Europeans believed in gold: They considered it to be very valuable. They wanted to trade gold with the world, and turns out, almost everyone else did, too.

What would have happened to the global economy if the Chinese had refused to accept payment in gold and silver? Yet why should Chinese, Indians, Muslims and Spaniards – who belonged to very different cultures that failed to agree about much of anything – nevertheless share the belief in gold?

Once trade is established, thanks to laws of supply and demand, the value of gold in India and the Mediterranean would be quite similar. The mere fact that Mediterranean people believed in gold would cause Indians to start believing in it as well.

When everything is convertible, and when trust depends on anonymous coins and cowry shells, it corrodes local traditions, intimate relations and human values, replacing them with the cold laws of supply and demand.

Empires

It is difficult to rule an empire in which every little district has its own set of laws, its own form of writing, its own language and its own money. Standardisation was a boon to emperors. Thus, empires spread a common culture.

A second and equally important reason was to gain legitimacy within the districts. This led to the Imperial Cycle.

The Imperial Cycle

- A small group establishes a big empire.

- An imperial culture is forged.

- The imperial culture is adopted by the subjects people.

- The subject people demand equal status in the name of common imperial values.

- The empires founders lose their dominance.

- The imperial culture continues to flourish and develop.

The global empire being forged before our eyes is not governed by any particular state or ethnic group. Much like the Late Roman Empire, it is ruled by a multi-ethnic elite, and is held together by a common culture and common interests. Throughout the world, more and more entrepreneurs, engineers, experts, scholars, lawyers and managers are called to join the empire. They must ponder whether to answer the imperial call or to remain loyal to their state and their people. More and more choose the empire.

This multi ethnic group of people come together to create a global empire – not via war, we are easily more sophisticated than that, but via economic and political powers.

As the cycle goes, people start freely adopting the ideals of this global empire, then they demand to be equals. Then the rulers die off and the people continue the empire.

Religion

Today religion is often considered a source of discrimination, disagreement and disunion. Yet, in fact, religion has been the third great unifier of humankind, alongside money and empires.

Since all social orders and hierarchies are imagined, they are all fragile, and the larger the society, the more fragile it is. The crucial historical role of religion has been to give superhuman legitimacy to these fragile structures. Religions assert that our laws are not the result of human caprice, but are ordained by an absolute and supreme authority. This helps place at least some fundamental laws beyond challenge, thereby ensuring social stability.

Religion can thus be defined as a system of human norms and values that is founded on a belief in a superhuman order. This involves two distinct criteria:

-

Religions hold that there is a superhuman order, which is not the product of human whims or agreements. Professional football is not a religion, because despite its many laws, rites and often bizarre rituals, everyone knows that human beings invented football themselves, and FIFA may at any moment enlarge the size of the goal or cancel the offside rule.

-

Based on this superhuman order, religion establishes norms and values that it considers binding. Many Westerners today believe in ghosts, fairies and reincarnation, but these beliefs are not a source of moral and behavioural standards. As such, they do not constitute a religion.

In order to unite under its aegis a large expanse of territory inhabited by disparate groups of human beings, a religion must possess two further qualities. First, it must espouse a universal superhuman order that is true always and everywhere. Second, it must insist on spreading this belief to everyone. So, it must be universal and missionary.

It’s interesting to watch the evolution of religion.

Expand: Evolution of Religion

Earlier, Animism was the dominant belief system. Human norms and values had to take into consideration the outlook and interests of a multitude of other beings, such as animals, plants, fairies and ghosts.

Local beliefs led to rules. Animals and plants were equal. Don’t cut down this fig tree lest the fig-tree spirit becomes angry. If the spirit stays happy, we’ll get lots of figs.

But with agriculture, humans started rearing plants and animals. They couldn’t harm us anymore. We obtained control. They switched from mysteries to possessions.

Much of ancient mythology is a legal contract in which humans promise everlasting devotion to the gods in exchange for mastery over plants and animals.

The Agricultural Revolution initially had a far smaller impact on the status of other members of the animist system, such as rocks, springs, ghosts and demons. However, these too gradually lost status in favour of the new gods.

As long as people lived their entire lives within limited territories of a few hundred square kilometers, most of their needs could be met by local spirits. But once kingdoms and trade networks expanded, people needed to contact entities whose power and authority encompassed a whole kingdom or an entire trade basin.

The attempt to answer these needs led to the appearance of polytheistic religions (from the Greek: poly = many, theos = god).

A terrible flood might wipe out billions of ants, grasshoppers, turtles, antelopes, giraffes and elephants, just because a few stupid Sapiens made the gods angry. Polytheism thereby exalted not only the status of the gods, but also that of humankind.

The fundamental insight of polytheism, which distinguishes it from monotheism, is that the supreme power governing the world is devoid of interests and biases, and therefore it is unconcerned with the mundane desires, cares and worries of humans.

Since polytheists believe, on the one hand, in one supreme and completely disinterested power, and on the other hand in many partial and biased powers, there is no difficulty for the devotees of one god to accept the existence and efficacy of other gods. Polytheism is inherently open-minded, and rarely persecutes ‘heretics’ and ‘infidels’.

Battle between good and evil for monotheism

Religion comes hand in hand with some fundamental concerns.

Why is there evil in the world? Why is there suffering? Why do bad things happen to good people?

Monotheists have to practice intellectual gymnastics to explain how an all-knowing, all-powerful and perfectly good God allows so much suffering in the world.

Dualism (one good and one evil god) has its own drawbacks. While solving the Problem of Evil, it is unnerved by the Problem of Order. If the world was created by a single God, it’s clear why it is such an orderly place, where everything obeys the same laws. But if Good and Evil battle for control of the world, who enforces the laws governing this cosmic war?

So, monotheism explains order, but is mystified by evil. Dualism explains evil, but is puzzled by order. There is one logical way of solving the riddle: to argue that there is a single omnipotent God who created the entire universe – and He’s evil. But nobody in history has had the stomach for such a belief.

Towards principles other than god

Gautama found that there was a way to exit this vicious circle of craving, disappointment and wanting more. If, when the mind experiences something pleasant or unpleasant, it simply understands things as they are, then there is no suffering. If you experience sadness without craving that the sadness go away, you continue to feel sadness but you do not suffer from it. There can actually be richness in the sadness. If you experience joy without craving that the joy linger and intensify, you continue to feel joy without losing your peace of mind.

A person who does not crave cannot suffer.

He encapsulated his teachings in a single law: suffering arises from craving; the only way to be fully liberated from suffering is to be fully liberated from craving; and the only way to be liberated from craving is to train the mind to experience reality as it is. This law, known as dharma or dhamma, is seen by Buddhists as a universal law of nature.

The modern age has witnessed the rise of a number of new natural-law religions, such as liberalism, Communism, capitalism, nationalism and Nazism. These creeds do not like to be called religions, and refer to themselves as ideologies.

Indeed, they are religions that worship humanity.

Scientific Revolution

The typical premodern ruler gave money to priests, philosophers and poets in the hope that they would legitimise his rule and maintain the social order. He did not expect them to discover new medications, invent new weapons or stimulate economic growth.

During the last five centuries, humans increasingly came to believe that they could increase their capabilities by investing in scientific research. This wasn’t just blind faith - it was proven empirically.

This belief came in part because modern science differs from all previous traditions of knowledge in three critical ways:

-

The willingness to admit ignorance. Modern science is based on the Latin injunction ignoramus – ‘we do not know’. It assumes that we don’t know everything. Even more critically, it accepts that the things that we think we know could be proven wrong as we gain more knowledge. No concept, idea or theory is sacred and beyond challenge.

-

The centrality of observation and mathematics. Having admitted ignorance, modern science aims to obtain new knowledge. It does so by gathering observations and then using mathematical tools to connect these observations into comprehensive theories.

-

The acquisition of new powers. Modern science is not content with creating theories. It uses these theories in order to acquire new powers, and in particular to develop new technologies.

It was inconceivable that the Bible, the Qur’an or the Vedas were missing out on a crucial secret of the universe – a secret that might yet be discovered by flesh-and-blood creatures.

One of the things that has made it possible for modern social orders to hold together (after the move away from religions holding together social order) is the spread of an almost religious belief in technology and in the methods of scientific research, which have replaced to some extent the belief in absolute truths.

Modern science has no dogma. Yet it has a common core of research methods, which are all based on collecting empirical observations – those we can observe with at least one of our senses – and putting them together with the help of mathematical tools.

For men of science, death is not an inevitable destiny, but merely a technical problem. People die not because the gods decreed it, but due to various technical failures – a heart attack, cancer, an infection. And every technical problem has a technical solution.

Further, most scientific studies are funded because somebody believes they can help attain some political, economic or religious goal.

Thus, scientific research can flourish only in alliance with some religion or ideology. The ideology justifies the costs of the research. In exchange, the ideology influences the scientific agenda and determines what to do with the discoveries.

Two forces in particular deserve our attention: imperialism and capitalism. The feedback loop between science, empire and capital has been history’s chief engine for the past 500 years.

Imperialism and science

The plant-seeking botanist and the colony-seeking naval officer shared a similar mindset. Both scientist and conqueror began by admitting ignorance – they both said, ‘I don’t know what’s out there.’ They both felt compelled to go out and make new discoveries. And they both hoped the new knowledge thus acquired would make them masters of the world.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europeans began to draw world maps with lots of empty spaces – one indication of the development of the scientific mindset, as well as of the European imperial drive. The empty maps were a psychological and ideological breakthrough, a clear admission that Europeans were ignorant of large parts of the world.

The discovery of America was the foundational event of the Scientific Revolution. It not only taught Europeans to favour present observations over past traditions, but the desire to conquer America also obliged Europeans to search for new knowledge at breakneck speed. If they really wanted to control the vast new territories, they had to gather enormous amounts of new data about the geography, climate, flora, fauna, languages, cultures and history of the new continent. Christian Scriptures, old geography books and ancient oral traditions were of little help.

Capitalism and science

Scientific research is usually funded by either governments or private businesses. When capitalist governments and businesses consider investing in a particular scientific project, the first questions are usually, ‘Will this project enable us to increase production and profits? Will it produce economic growth?’ A project that can’t clear these hurdles has little chance of finding a sponsor. No history of modern science can leave capitalism out of the picture.

However, the feedback loop between capitalism and science runs much deeper. Capitalism wouldn’t be possible without science, either. It’s based on a belief in the future - the future will be better than the present, thanks to science.

A society of wolves would be extremely foolish to believe that the supply of sheep would keep on growing indefinitely.

There’s much more to say about Capitalism. So much more, that I’ve separated it into a post of its own. Read here: A Short History of Capitalism

Industrial Revolution

The modern economy grows thanks to our trust in the future and to the willingness of capitalists to reinvest their profits in production. Yet that does not suffice. Economic growth also requires energy and raw materials, and these are finite. When and if they run out, the entire system will collapse.

For millennia prior to the Industrial Revolution, humans already knew how to make use of a large variety of energy sources. They burned wood in order to smelt iron, heat houses and bake cakes. Sailing ships harnessed wind power to move around, and watermills captured the flow of rivers to grind grain. Yet all these had clear limits and problems. Trees were not available everywhere, the wind didn’t always blow when you needed it, and water power was only useful if you lived near a river.

An even bigger problem was that people didn’t know how to convert one type of energy into another.

Since human and animal bodies were the only energy conversion device available, muscle power was the key to almost all human activities. Everyone was fuelled by solar energy – captured and packaged in wheat, rice and potatoes.

The invention of the steam engine brought about the Industrial Revolution.

You burn some kind of fuel, such as coal, and use the resulting heat to boil water, producing steam. As the steam expands it pushes a piston. The piston moves, and anything that is connected to the piston moves with it. You have converted heat into movement.

In the decades that followed, British entrepreneurs improved the efficiency of the steam engine, brought it out of the mineshafts, and connected it to looms and gins. This revolutionised textile production, making it possible to produce ever-larger quantities of cheap textiles.

People became obsessed with the idea that machines and engines could be used to convert one type of energy into another. Any type of energy, anywhere in the world, might be harnessed to whatever need we had, if we could just invent the right machine.

Another crucial discovery was the internal combustion engine, which took little more than a generation to revolutionise human transportation and turn petroleum into liquid political power. Petroleum had been known for thousands of years, and was used to waterproof roofs and lubricate axles. Yet until just a century ago nobody thought it was useful for much more than that. The idea of spilling blood for the sake of oil would have seemed ludicrous. You might fight a war over land, gold, pepper or slaves, but not oil.

At heart, the Industrial Revolution has been a revolution in energy conversion. It has demonstrated again and again that there is no limit to the amount of energy at our disposal. Or, that the only limit is set by our ignorance. Every few decades we discover a new energy source, so that the sum total of energy at our disposal just keeps growing.

The result of the industrial revolution was an explosion in human productivity. The explosion was felt first and foremost in agriculture. Usually, when we think of the Industrial Revolution, we think of an urban landscape of smoking chimneys, or the plight of exploited coal miners sweating in the bowels of the earth. Yet the Industrial Revolution was above all else the Second Agricultural Revolution.

Without the industrialisation of agriculture the urban Industrial Revolution could never have taken place – there would not have been enough hands and brains to staff factories and offices.

Aftereffects of Industry

The Industrial Revolution turned the timetable and the assembly line into a template for almost all human activities. Shortly after factories imposed their time frames on human behaviour, schools too adopted precise timetables, followed by hospitals, government offices and grocery stores. Even in places devoid of assembly lines and machines, the timetable became king. If the shift at the factory ends at 5 p.m., the local pub had better be open for business by 5:02.

This modest beginning spawned a global network of timetables, synchronised down to the tiniest fractions of a second. When the broadcast media – first radio, then television – made their debut, they entered a world of timetables and became its main enforcers and evangelists.

Along with adapting to industrial time, this revolution brought about urbanisation, the disappearance of the peasantry, the rise of the industrial proletariat, the empowerment of the common person, democratisation, youth culture and the disintegration of patriarchy.

Most of the traditional functions of families and communities were handed over to states and markets.

Collapse of family

Village life involved many transactions but few payments. There were some markets, of course, but their roles were limited. You could buy rare spices, cloth and tools, and hire the services of lawyers and doctors. Yet less than 10 per cent of commonly used products and services were bought in the market. Most human needs were taken care of by the family and the community.

Traditional agricultural economies had few surpluses with which to feed crowds of government officials, policemen, social workers, teachers and doctors. Consequently, most rulers did not develop mass welfare systems, health-care systems or educational systems.

This was left for the family and communities.

There wasn’t much a person renouncing his family could do. In order to survive, such a person had to find an alternative family or community. Boys and girls who ran away from home could expect, at best, to become servants in some new family. At worst, there was the army or the brothel.

All this changed dramatically over the last two centuries. The Industrial Revolution gave the market immense new powers, provided the state with new means of communication and transportation, and placed at the government’s disposal an army of clerks, teachers, policemen and social workers. At first the market and the state discovered their path blocked by traditional families and communities who had little love for outside intervention. Parents and community elders were reluctant to let the younger generation be indoctrinated by nationalist education systems, conscripted into armies or turned into a rootless urban proletariat.

The state and the market approached people with an offer that could not be refused. ‘Become individuals,’ they said. ‘Marry whomever you desire, without asking permission from your parents. Take up whatever job suits you, even if community elders frown. Live wherever you wish, even if you cannot make it every week to the family dinner. You are no longer dependent on your family or your community. We, the state and the market, will take care of you instead. We will provide food, shelter, education, health, welfare and employment. We will provide pensions, insurance and protection.’

Movement from war to peace

With industry and trade, countries moved from a plundering focused mindset to a protection focused mindset.

Four factors led to peace.

- Threat of nuclear holocaust.

- Declining profits of war with no new territories.

- Flourishing trade which increased cost of war.

- International connections between countries.

There is a positive feedback loop between all these four factors. The threat of nuclear holocaust fosters pacifism; when pacifism spreads, war recedes and trade flourishes; and trade increases both the profits of peace and the costs of war.

Over time, this feedback loop creates another obstacle to war, which may ultimately prove the most important of all. The tightening web of international connections erodes the independence of most countries, lessening the chance that any one of them might single-handedly let slip the dogs of war. Most countries no longer engage in full-scale war for the simple reason that they are no longer independent.

The End of Homo Sapiens

The beauty of Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection is that it does not need to assume an intelligent designer to explain how giraffes ended up with long necks, or why lean and fast chicken survive.

Biologists the world over are locked in battle with the intelligent-design movement, which opposes the teaching of Darwinian evolution in schools and claims that biological complexity proves there must be a creator who thought out all biological details in advance. The biologists are right about the past, but the proponents of intelligent design might, ironically, be right about the future.

The first light for intelligent design appeared about 10,000 years ago, during the Agricultural Revolution. Sapiens who dreamed of fat, slow-moving chickens discovered that if they mated the fattest hen with the slowest cock, some of their offspring would be both fat and slow. If you mated those offspring with each other, you could produce a line of fat, slow birds. It was a race of chickens unknown to nature, produced by the intelligent design not of a god but of a human.

History teaches us that what seems to be just around the corner may never materialise due to unforeseen barriers, and that other unimagined scenarios will in fact come to pass.

What we should take seriously is the idea that the next stage of history will include not only technological and organisational transformations, but also fundamental transformations in human consciousness and identity.

We might stop being homo sapiens.