Most programming languages support a small number of popular, stable application frameworks. Objective-C and Swift apps use Apple’s excellent Cocoa framework. Ruby apps more often than not use Rails. Java has a handful of established web app frameworks, and they come and go relatively slowly.

In the meantime, the latest and greatest JavaScript framework comes around every sixteen minutes.

Studies show that a todo list is the most complex JavaScript app you can build before a newer, better framework is invented. Luckily, there’s an excellent site called TodoMVC dedicated to comparing JavaScript frameworks by way of todo sample projects. There, you can see how 63 JavaScript app frameworks’ todo examples compare to just jQuery or vanilla JavaScript. If you think 63 frameworks are a lot, you ain’t seen nothing yet: the TodoMVC team gets multiple pull requests weekly from people flogging new JavaScript frameworks.

For example, the most recent TodoMVC pull request, as of this writing, wants to add Riot.js 2.0. What is Riot.js 2.0, you ask? Apparently, it’s the second version of something called Riot.js, an app framework that’s like React.js, but better in some ways that are definitely important. “But wait,” you may ask, “didn’t React like just come out and isn’t even 1.0 yet? How can a thing based on it be 2.0 already?!” The answer, my friend, is JavaScript.

Why is the JavaScript framework environment so unstable? What is driving this insanity? Why are Ruby developers using Rails 4.2 but client-side developers are hyping boron.js 0.2.1?

The problem is, as always, the browser. The modern web browser is an incredible feat of engineering, especially considering its humble roots as a way to display simple documents. There is definitely a substantial amount of framework turnover in the node/io.js community, but it’s nothing compared to the zoo that is the browser app framework world. The wild instability of the client-side JavaScript landscape is a product of the browser: both its historical limitations and its incredible rate of improvement.

The browser is most ubiquitous app runtime in history by a wide margin, and to write applications for it you need to write JavaScript. As a consequence, JavaScript is the least elective programming language in the world – most people who are writing client-side JavaScript applications are not doing so because they chose JavaScript, but because they chose client-side web development. These people come from a wide variety of backgrounds, and have a wide variety of goals. This constant inflow of new ideas and interests has made the JavaScript community unusually diverse.

Meanwhile, the browser itself changes far more rapidly and unpredictably than the underlying languages on which other frameworks are built. The browser has changed more since Backbone.js debuted in 2010 than Objective-C has changed since Cocoa debuted all the way back in 1988. Browser improvements that inspire new generations of frameworks happen constantly.

These inputs fuel an incredible amount of experimentation, excitement, and adaptation. Every day new frameworks, new approaches, and new tools erupt from the geyser we call Github. Every year there are more instant-classic JSConf talks about crazy new ideas, impressive new browser features, and rethinking best practices. This beautiful chaos is exciting in a way that I’ve never seen in another developer community.

Unfortunately, while the community is busy driving new features and new frameworks, the browser is is busy killing them.

Unlike the frameworks we use in C++ or Swift, the entirety of your app framework must be downloaded, parsed, and turned into machine code before users even see your app. Caching and offline access continue to improve, but the very real constraints on bandwidth, latency, memory, and loading time are a huge challenge for the kind of huge app frameworks that we take for granted in native app development.

This is especially true on mobile, where the already problematic constraints of memory, CPU, and network bandwidth can be crippling. While JavaScript is now a remarkably fast language, the ubiquity of the web means that your code and framework can be downloaded and run in some incredibly hostile environments. Frameworks that can take advantage of Chrome Canary’s supernatural powers on a Mac Pro aren’t going to enjoy themselves on “Browser” on an old Acer EvoAMAZE Plus 3G E.

The churning seas on which client-side frameworks sail are especially treacherous for large, ambitious frameworks that try to create a rich environment and UI library for building apps the way we do natively.

When SproutCore and Cappuccino appeared in 2007, I was totally sold by the amazing demos. I’d thought Moore’s law had finally delivered stable, featureful JavaScript frameworks for building beautiful desktop-like apps in the browser. Then I spent two years shipping stuff with SproutCore, dealing with megabytes’ worth of somebody else’s JavaScript, wrestling with weird technical choices necessitated by horrible DOM performance on IE7, and somehow cramming the whole thing into the iPad’s 256MB of RAM. Meanwhile, the documentation never caught up to the pace of breaking changes, and performance was a constant battle. Before long, the dream felt more like an evolutionary dead end.

While in many ways I still dream of a framework that could deliver on the promises that SproutCore and Cappuccino made, I now have much more respect for how hard such a thing is to build, especially in JavaScript. The same flexible, untyped nature that makes JavaScript fun to write a microframework in makes it kind of unpleasant to learn or maintain a large framework in. While the strong typing of native app frameworks can feel like a drag on tiny projects, it makes their often-massive APIs easy to explore and use effectively: just tab-complete your way to victory.

A deprecated API in the Cocoa framework just means that a warning comes up when I open my project, and sometimes I can even right-click to replace the old way of doing things with the new way. Meanwhile in JavaScript, poking around in the Webkit REPL to find APIs you might make use of is a good way to find unsupported accidentally public APIs that will blow up your app at runtime after some point update of your framework.

All these forces – the rapid changes, the diverse needs, the hostile environment, and the loose language features – make large, feature-rich JavaScript frameworks slow, lumbering prey. A horde of young, nimble microframeworks swarm them, take them down, and fight over the meal. Modularity and componentization reigns.

A world dominated by endless tiny frameworks actually works okay for JavaScript experts and consultants. We become skilled at mixing and matching components, are able to spend time keeping up to date on the latest options and their relative strengths, and gain a lot of fodder for our conference talks. Yet for those who are new to JavaScript or who aren’t full-time client-side developers, any given tiny framework can’t possibly solve the wide range of problems that JavaScript developers struggle with. Product companies building large, long-lived client-side apps need to settle on some framework, and live with the consequences for years as they discover its limitations.

The well-regarded Mithril.js framework is only 5kb. That’s great for load and parse time, but it necessarily can’t solve a rich array of problems. Rails, by contrast, has more than 100x as much code. Just ActiveRecord is 1274kb! In the browser, you can’t sanely use a 1.2MB framework, and so the proliferation continues.

Neck deep in frameworks, choosing one we’re actually happy with becomes virtually impossible. The Paradox of Choice means that knowing you’re probably not using the right framework causes endless cognitive dissonance. Ironically, this dissatisfaction drives even more people to create their own frameworks.

Framework fatigue has driven down the number of frameworks that JavaScript developers actually try. Who is going to actually build a non-trivial application with Dojo, YUI, ExtJS, jQuery UI, Backbone, Ember, Cappuccino, SproutCore, GWT – oh man remember GWT? – Angular, Sencha, jQuery Mobile, Knockout, Meteor, Ampersand, Flight, Mithril, Polymer, React and Flux? Seriously?

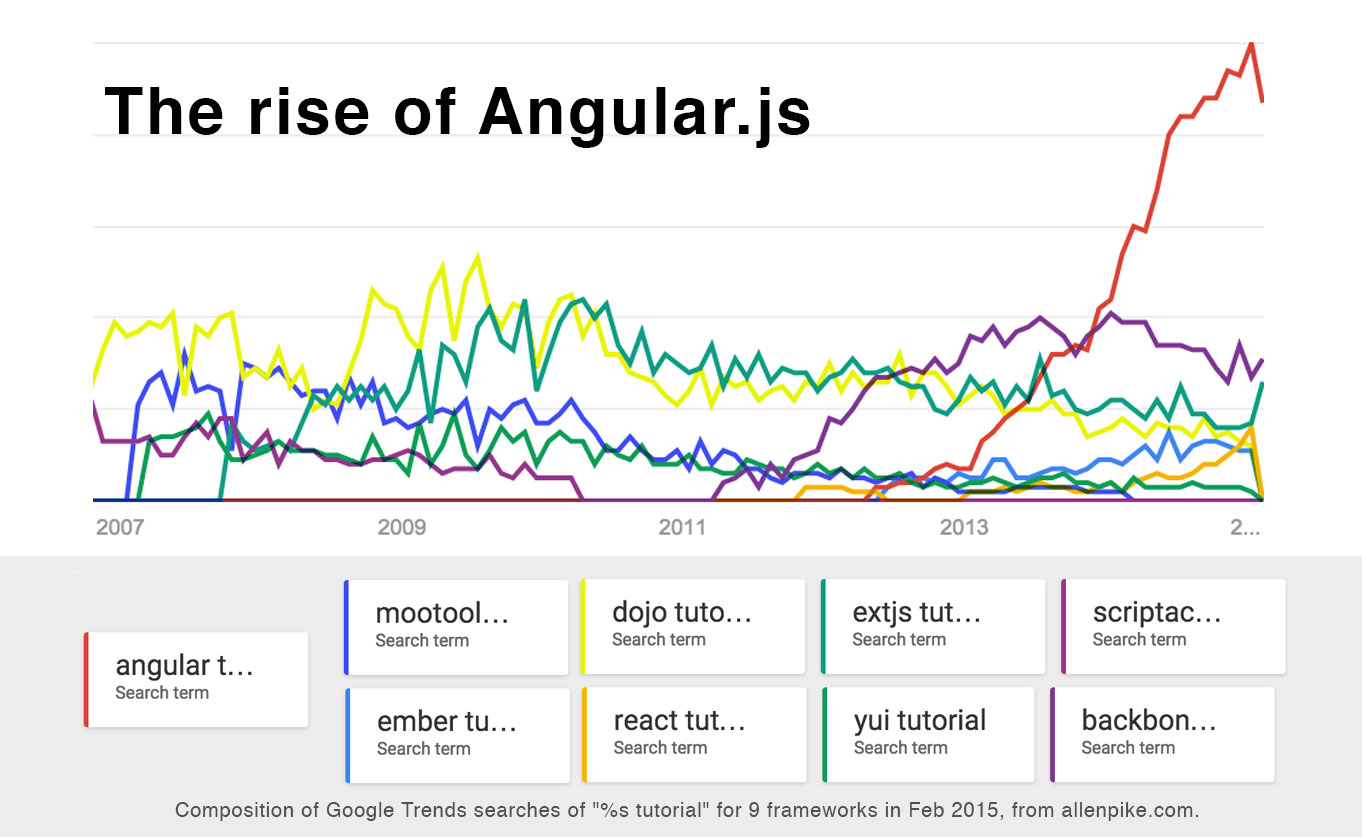

Nobody can try all the popular options, but everybody wishes for consolidation and more wood behind fewer frameworks. As such, a lot of developers have fallen into a pattern: avoid learning a new framework until it seems like one is finally ascending to the throne as the widely popular, exceptionally capable, “won’t get you fired” choice for building JavaScript frameworks. While Google Trends is no double-blind study, it seems clear that interest in Angular has far surpassed that of any historical web app framework. After a decade of chaos, it finally looks like one we’ve found the chosen one!

Yes, Angular,js, the framework that I initially described in 2009 as “unreasonably weird” seems to have achieved a level of popularity that no JS app framework ever has. Between serious support from Google, an easy ramp-up path, and a rich community, Angular looks poised to finally settle the…

Wait, what’s that? The Angular team has decided that Angular 2 will not be compatible with Angular 1.x, and there will be no easy upgrade path?

Developers familiar with the Angular 1.X will encounter a drastically different looking framework and will need to learn a new architecture.

Oof.

Perhaps we should just resign ourselves to it always being this way. While I’ve long argued that creating your own JavaScript framework out of a microframework and a DOM library is madness, maybe it’s the least bad option. Maybe the quirks of the language and the constraints of the browser make a sophisticated but bulletproof framework like Cocoa or Rails just kind of impossible.

Maybe I should just call off the hunt. Though, people do seem pretty excited about React.js. They have some smart developers and exciting ideas, at least from what I’ve seen.

You know, maybe I should build something new with it and see what it’s like. Maybe… maybe it’s the one.