Source originale du contenu

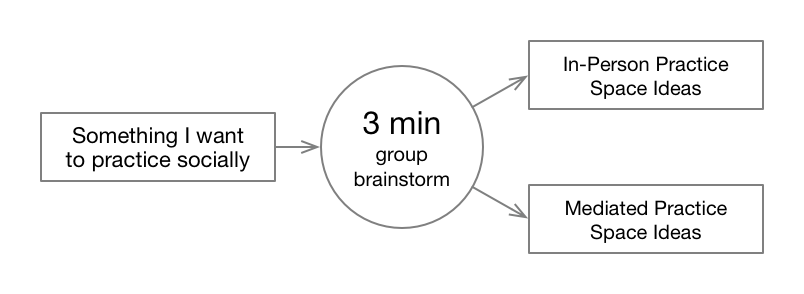

In my note to Mark Zuckerberg (which you probably want to read first), I urged his team and other technologists to reimagine their products as “practice spaces” — virtual places where people practice the kinds of acts and relationships they find meaningful.

In this post, I will show how this is concretely possible.

How to Design Social Systems (Without Causing Depression and War)

Here I’ll present a way to think about social systems, meaningful interactions, and human values that brings these often-hazy concepts into focus. It’s also, in a sense, an essay on human nature: on what humans need to live well. It’s organized in three sections:

- Reflection and Experimentation. How do people decide which values to bring to a situation?

- Practice Spaces. Can we look at social systems and see which values they support and which they undermine?

- Sharing Wisdom. What are the meaningful conversations that we, as a culture, are starved for?

I’ll introduce these concepts and their implications for design. I will show how, applied to social media, they address issues like election manipulation, fake news, internet addiction, teen depression & suicide, and various threats to children. At the end of the post, I’ll discuss the challenges of doing this type of design at Facebook and in other technology teams.

Reflection and Experimentation

As I tried to make clear in my letter, meaningful interactions and time well spent are a matter of values. For each person, certain kinds of acts are meaningful, and certain ways of relating. Unless the software supports those acts and ways of relating, there will be a loss of meaning.

In the section below about practice spaces, I’ll cover how to design software that supports the users’ values in this way. But first, let’s talk about how people pick their values in the first place.

We often don’t know how we want to act or relate in a particular situation. Not immediately, at least.

When we approach an event (a conversation, a meeting, a morning, a task), there’s a process — mostly unconscious — by which we decide how we want to be (for example, whether we want to be open, generous, strict, clear, or honest).

It’s important to understand this process, and how designs can interrupt it. As we’ll see, such interruptions can lead to doing things we regret. They can lead to internet addiction, to bullying and trolling, and to the problems teens are having online.

The Process

To start, let’s imagine someone going through this process; someone for whom it’s a big part of life.

So, imagine a teenager. She is sorting out how she wants to be, socially. She is exploring ideas about how people ought to act (intelligent, feminine, polite, etc) and questioning them. In different situations, she tries out different ways of being intelligent, feminine, or polite, and sees what happens. She may at first imagine she wants to be infinitely feminine or infinitely polite, but in the context of real choices, these values no longer seem right. She reflects on who she wants to be, and how she wants to live.

We all make small choices, everyday, using the same process the teenager used for these big choices. When we approach a conversation or meeting, for instance, we may need to decide how to balance honesty and tact. Even with these small choices, we need to experiment and reflect.

Until we do all of this (experiment and reflect in the context of real choices) we might think we have certain values, but we haven’t really gotten clear on how we want to relate or act. Certain values (eating kale, recycling, supporting the troops, radical honesty) won’t survive exposure to real choices. Other values will.

This process of sorting ourselves out can be intuitive, nonverbal, and unconscious, but it is vital.¹ If we don’t approach situations with the values that are right for us, it’s hard to feel good about what we do.

Obstacles

The following circumstances interfere with experimentation, with reflection, or with real choices:

- High stakes. When deviation from norms becomes disastrous in some way — for instance, with very high reputational stakes — people are afraid to experiment. People need space to make mistakes and systems and social scenes with high consequences interfere with this.

- Low agency. To put values to the test, a person needs discretion over the manner of their work: they need to experiment with moral values, aesthetic values, and other guiding ideas. Some environments — many of them corporate — make no room for being guided by one’s own moral or aesthetic ideas.

- Disconnection. One way we judge the values we’re experimenting with is via exposure to their consequences. We all need to know how others feel when we treat them one way or another, to help us decide how we want to treat them. Similarly, an architect needs to know what it’s like to live in the buildings she designs. When the consequences of our actions are hidden, we can’t sort out what’s important.²

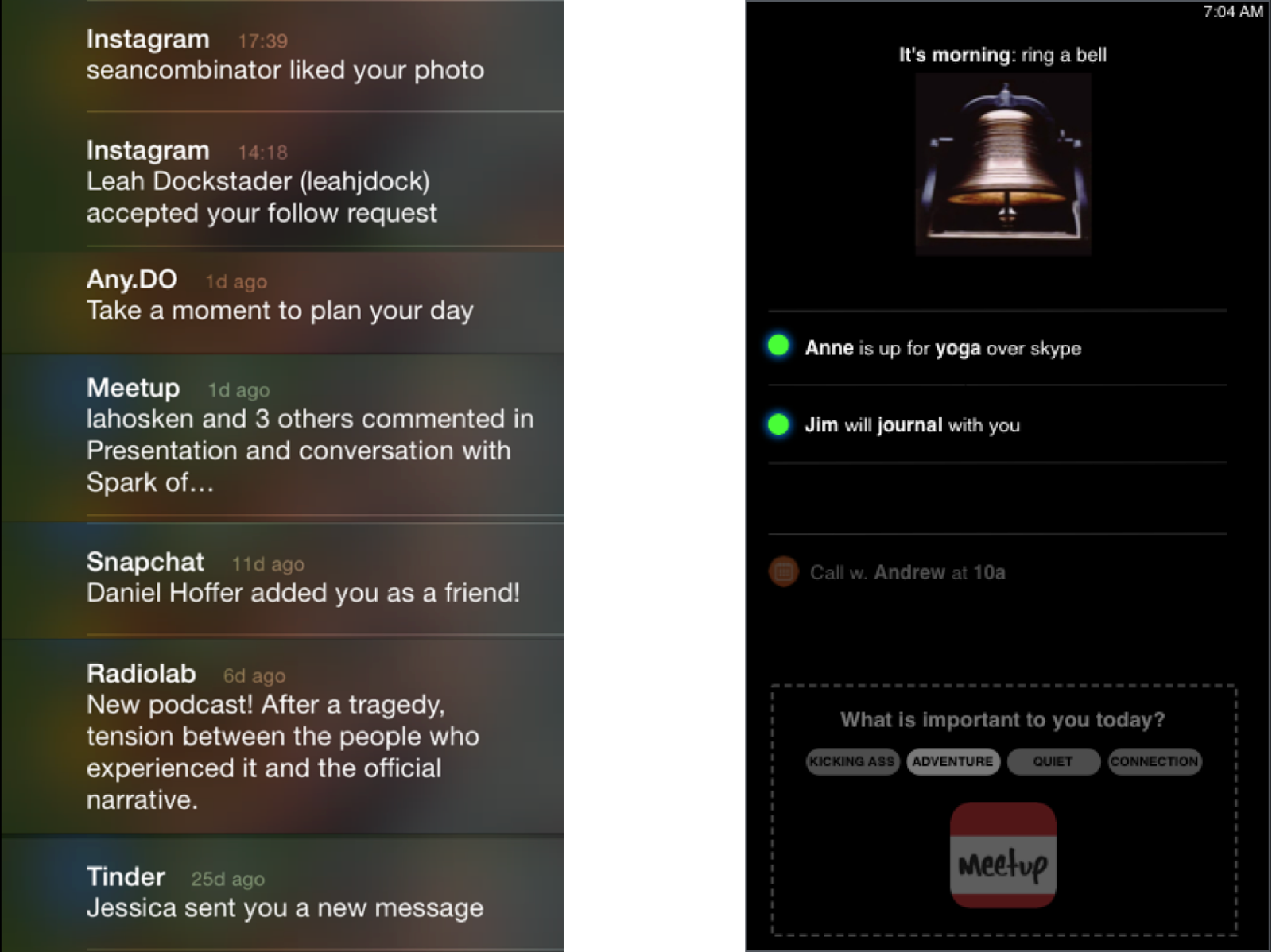

- Distraction and overwork. We also lose the capacity to sort out our values when reflection becomes impossible. This is the major cost of noisy environments, infinite entertainment, push notifications, and some types of poverty.

- Lack of faith in reflection. Finally, people can come to consider reflection to be useless — or to be avoided — even though it is so natural. The emotions which trigger reflection, including doubt and confusion, can be brushed away as distractions. One way this happens is if people view their choices through a behaviorist lens: as determined by habits, reinforcement learning, or permanent drives.³ This makes it seem like people don’t have values at all, only habits, tastes, and goals. Experimentation and reflection seem useless.

Software-based social spaces can be disastrous for experimentation and reflection. The normal iOS lock screen suffers from three of the problems above: low agency, disconnection from consequences, and distraction. Below, it has been redesigned to address these problems.

Certain kinds of conversation have migrated to private group messaging (like WhatsApp and Messenger), away from virality-based feeds (like Twitter, News Feed, and increasingly, Stories). Here’s one reasons for this: the feeds are horrible for experimenting with who we are. The stakes are too high. They seem especially bad for women, for teens, and for celebrities—which may partly explain the rise in teen suicide—but they're bad for all of us.

There’s a similar problem with online bullying, trolling, and political outrage. Many bullies and trolls would embrace other values if they had a chance to reflect and were better exposed to consequences.

For users to have meaningful interactions and feel their time was well spent, they need to approach situations in a way they believe in. They need space to experiment and reflect. All of us (not just bullies and trolls) would use the Internet differently if we had more room for reflection.

But this is not enough: even with our values in order, a social environment can undermine our plans.

Practice Spaces

Every social system makes some values easier to practice, and other values harder.

Most platforms encourage us to act against our values: less humbly, less honestly, less thoughtfully, and so on. Using these platforms while sticking to our values would mean constantly fighting their design. Unless we’re prepared for that fight, we’ll regret our choices.

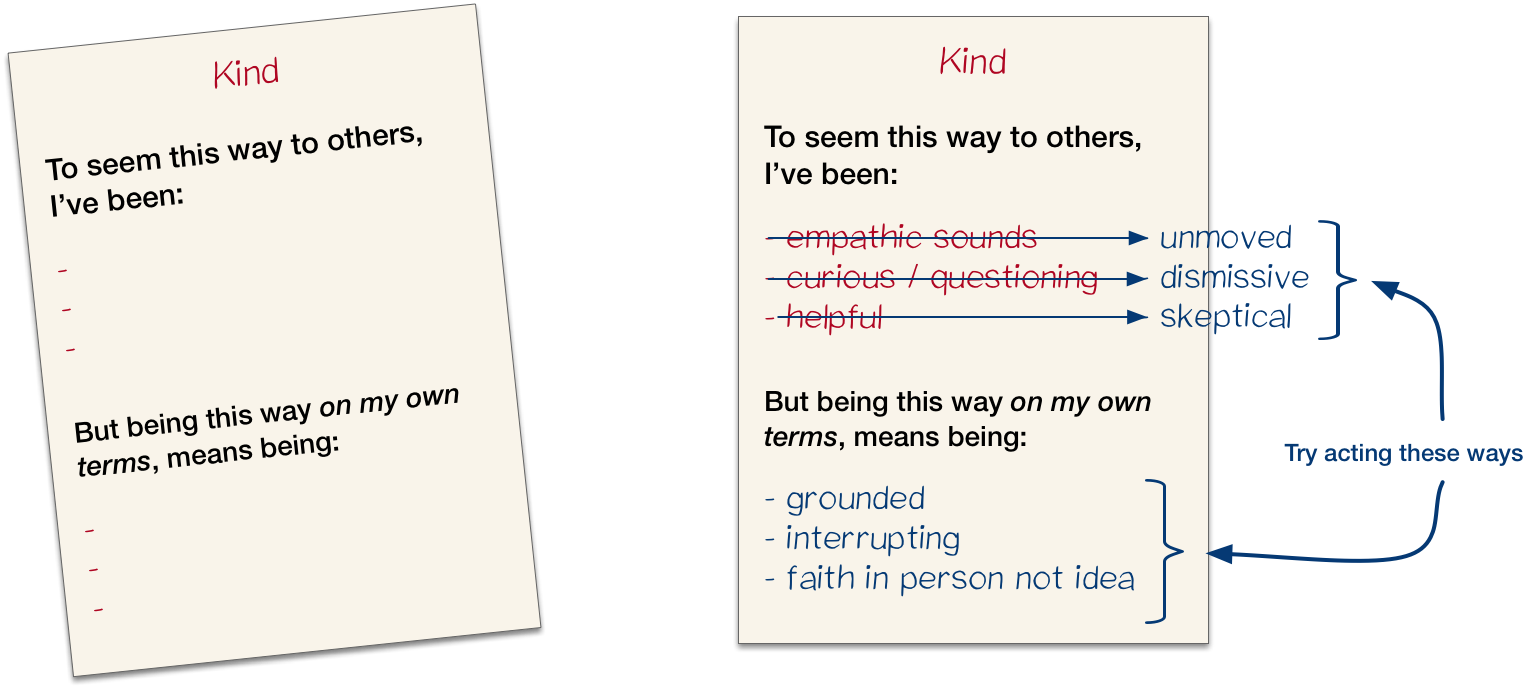

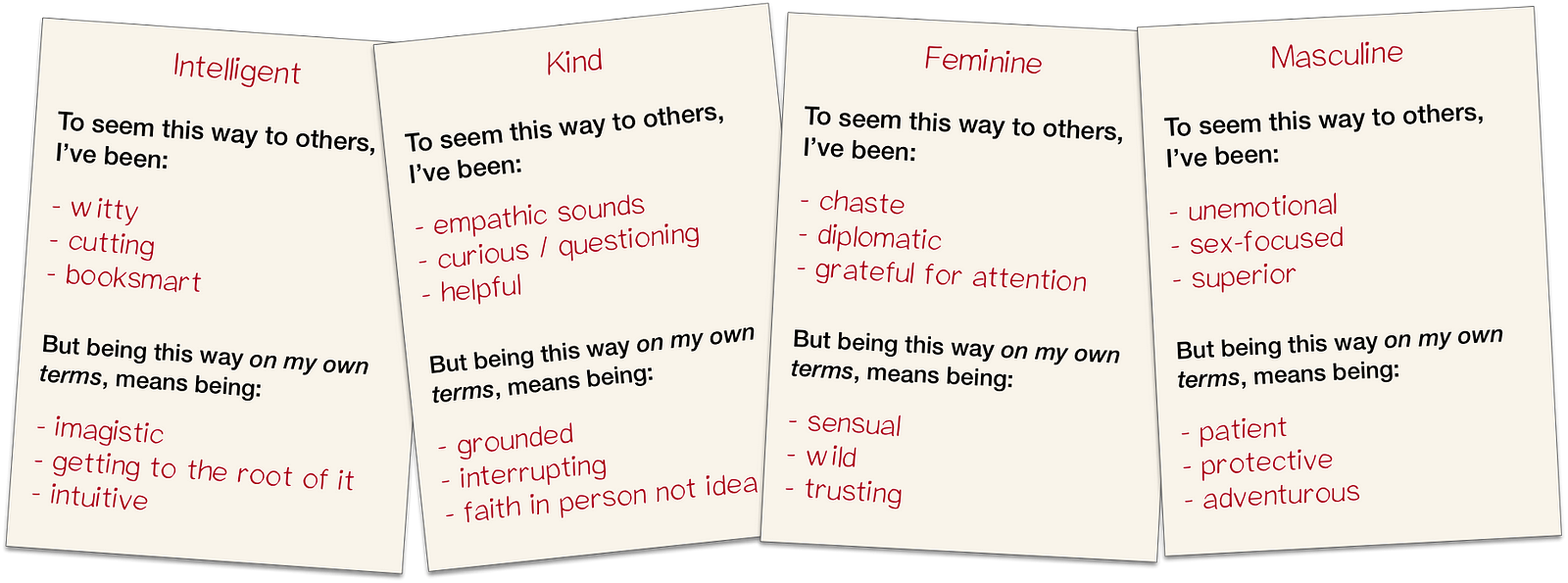

Designers can address this by understanding what’s difficult about relating according to different values (what’s difficult about being honest, being open, and so on), and by recognizing what features of social spaces can make it easier. I’ll explain what this means and show how it leads to new designs.

Difficult Parts

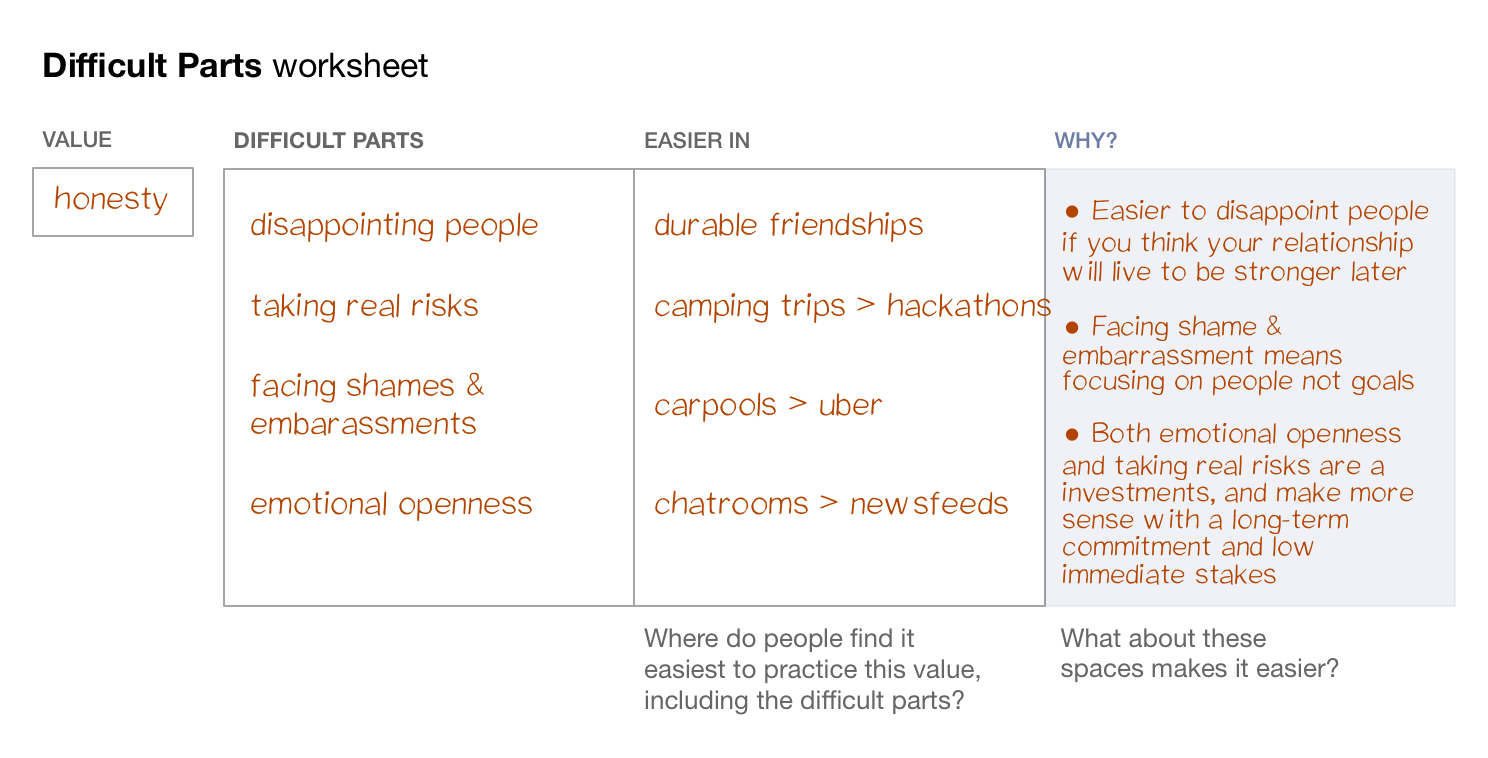

When users want to relate according to a particular value, what is hard about doing that?

For instance, what’s difficult about being honest? Sometimes, being honest means disappointing people, facing embarrassment and shame, or showing a vulnerable emotion. Each of these is easier in some kinds of social spaces than in others.

Features of Good Practice Spaces

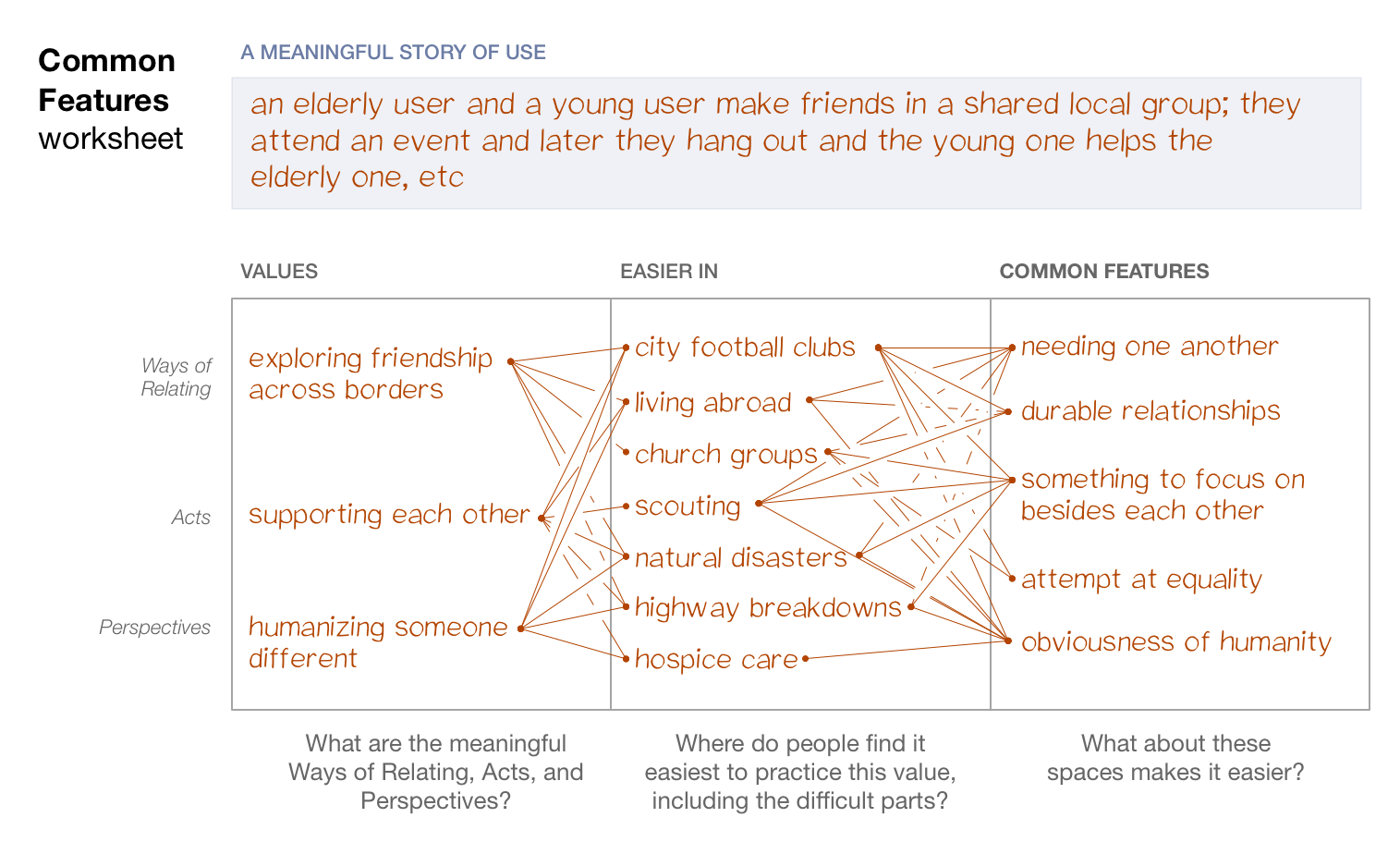

Designers can investigate—for each value their users have—what it is about some social spaces that make relating in that way easier.

For example, if an Instagram⁵ user valued being creative, being honest, or connecting adventurously, then designers would need to ask: what kinds of social environments make it easier to be creative, to be honest, or to connect adventurously? They could make a list of places where people find these things easier: camping trips, open-mics, writing groups, and so on.

Next, the designers would ask: which features of these environments make them good at this? For instance, when someone is trying to be creative, do mechanisms for showing relative status (like follower counts) help or hurt? How about when someone wants to connect adventurously? Or, with being creative, is this easier in a small group of close connections, or a large group of distant ones? And so on.

To take another example, if a News Feed user believes in being open-minded, designers would ask which social environments make this easier. Having made such a list, they would look for common features. Perhaps it’s easier to be open-minded when you remember something you respect about a person’s previous views. Or, perhaps it’s easier when you can tell if the person is in a thoughtful mood by reading their body language. Is open-mindedness more natural when those speaking have to explicitly yield time for others to respond? Designers would have to find out.⁶