Source originale du contenu

Aren’t classical inheritance and prototypal inheritance really the same thing, just a stylistic preference?

No.

Classical and prototypal inheritance are fundamentally and semantically distinct.

There are some defining characteristics between classical inheritance and prototypal inheritance. For any of this article to make sense, you must keep these points in mind:

In class inheritance, instances inherit from a blueprint (the class), and create sub-class relationships. In other words, you can’t use the class like you would use an instance. You can’t invoke instance methods on a class definition itself. You must first create an instance and then invoke methods on that instance.

In prototypal inheritance, instances inherit from other instances. Using delegate prototypes (setting the prototype of one instance to refer to an examplar object), it’s literally Objects Linking to Other Objects, or OLOO, as Kyle Simpson calls it. Using concatenative inheritance, you just copy properties from an exemplar object to a new instance.

It’s really important that you understand these differences. Class inheritance by virtue of its mechanisms create class hierarchies as a side-effect of sub-class creation. Those hierarchies lead to arthritic code (hard to change) and brittleness (easy to break due to rippling side-effects when you modify base classes).

Prototypal inheritance does not necessarily create similar hierarchies. I recommend that you keep prototype chains as shallow as possible. It’s easy to flatten many prototypes together to form a single delegate prototype.

TL;DR:

- A class is a blueprint.

- A prototype is an object instance.

Aren’t classes the right way to create objects in JavaScript?

No.

There are several right ways to create objects in JavaScript. The first and most common is an object literal. It looks like this (in ES6):

Of course, object literals have been around a lot longer than ES6, but they lack the method shortcut seen above, and you have to use `var` instead of `let`. Oh, and that template string thing in the `.describe()` method won’t work in ES5, either.

You can attach delegate prototypes with `Object.create()` (an ES5 feature):

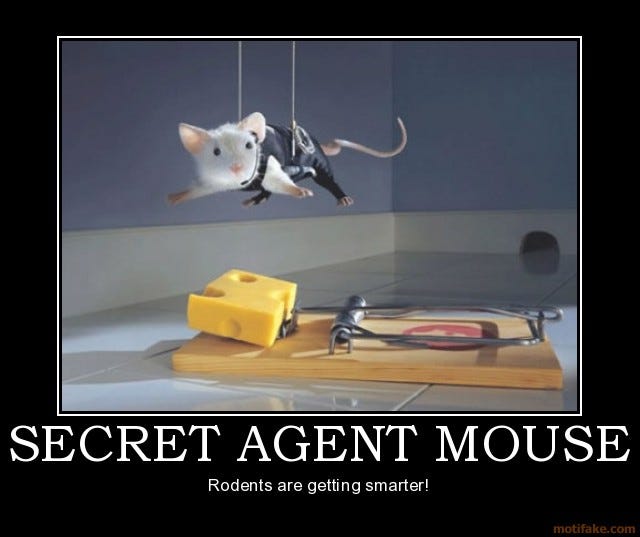

Let’s break this one down a little. `animal` is a delegate prototype. `mouse` is an instance. When you try to access a property on `mouse` that isn’t there, the JavaScript runtime will look for the property on `animal` (the delegate).

`Object.assign()` is a new ES6 feature championed by Rick Waldron that was previously implemented in a few dozen libraries. You might know it as `$.extend()` from jQuery or `_.extend()` from Underscore. Lodash has a version of it called `assign()`. You pass in a destination object, and as many source objects as you like, separated by commas. It will copy all of the enumerable own properties by assignment from the source objects to the destination objects with last in priority. If there are any property name conflicts, the version from the last object passed in wins.

`Object.create()` is an ES5 feature that was championed by Douglas Crockford so that we could attach delegate prototypes without using constructors and the `new` keyword.

I’m skipping the constructor function example because I can’t recommend them. I’ve seen them abused a lot, and I’ve seen them cause a lot of trouble. It’s worth noting that a lot of smart people disagree with me. Smart people will do whatever they want.

Wise people will take Douglas Crockford’s advice:

“If a feature is sometimes dangerous, and there is a better option, then always use the better option.”

Don’t you need a constructor function to specify object instantiation behavior and handle object initialization?

No.

Any function can create and return objects. When it’s not a constructor function, it’s called a factory function.

The Better Option

I usually don’t name my factories “factory” — that’s just for illustration. Normally I just would have called it `mouse()`.

Don’t you need constructor functions for privacy in JavaScript?

No.

In JavaScript, any time you export a function, that function has access to the outer function’s variables. When you use them, the JS engine creates a closure. Closures are a common pattern in JavaScript, and they’re commonly used for data privacy.

Closures are not unique to constructor functions. Any function can create a closure for data privacy:

Does `new` mean that code is using classical inheritance?

No.

The `new` keyword is used to invoke a constructor. What it actually does is:

- Create a new instance

- Bind `this` to the new instance

- Reference the new object’s delegate [[Prototype]] to the object referenced by the constructor function’s `prototype` property.

- Names the object type after the constructor, which you’ll notice mostly in the debugging console. You’ll see `[Object Foo]`, for example, instead of `[Object object]`.

- Allows `instanceof` to check whether or not an object’s prototype reference is the same object referenced by the .prototype property of the constructor.

`instanceof` lies

Let’s pause here for a moment and reconsider the value of `instanceof`. You might change your mind about its usefulness.

Important: `instanceof` does not do type checking the way that you expect similar checks to do in strongly typed languages. Instead, it does an identity check on the prototype object, and it’s easily fooled. It won’t work across execution contexts, for instance (a common source of bugs, frustration, and unnecessary limitations). For reference, an example in the wild, from bacon.js.

It’s also easily tricked into false positives (and more commonly) false negatives from another source. Since it’s an identity check against a target object’s `.prototype` property, it can lead to strange things:

> function foo() {}

> var bar = { a: ‘a’};

> foo.prototype = bar; // Object {a: “a”}

> baz = Object.create(bar); // Object {a: “a”}

> baz instanceof foo // true. oops.

That last result is completely in line with the JavaScript specification. Nothing is broken — it’s just that `instanceof` can’t make any guarantees about type safety. It’s easily tricked into reporting both false positives, and false negatives.

Besides that, trying to force your JS code to behave like strongly typed code can block your functions from being lifted to generics, which are much more reusable and useful.

`instanceof` limits the reusability of your code, and potentially introduces bugs into the programs that use your code.

`instanceof` lies.

Ducktype instead.