The Vibes Theory of Organisational Design

The bigger the group, the more rules they need. Can we do better than written agreements?

In this article I’m going to bite off some big ideas, musing on the limitations of encoding agreements in text. To keep it grounded, I’ll illustrate the ideas with real-world stories. I’ll include a couple of practical tools you can try right away. But mostly, this is a reflection from the frontiers of decentralised organising: the ideas here probably only reflect the reality of a tiny number of organisations. It’s highly speculative, subjective, exploratory. I’m not educated in social psychology so I haven’t quoted any sources and I’ve probably mangled the science. In other words: don’t try this at home. The invitation is to put on your safety gear and come exploring with me…

First I’ll set some context, exploring why groups create written rules as they grow. Then, I’ll name some of the dysfunctions that emerge from the rule-setting process. Then I speculate that we might get different outcomes if we used something other than a written rule book. Here goes!

Where does togetherness come from?

Lately I’ve been reflecting deeply on this question: what holds a group together?

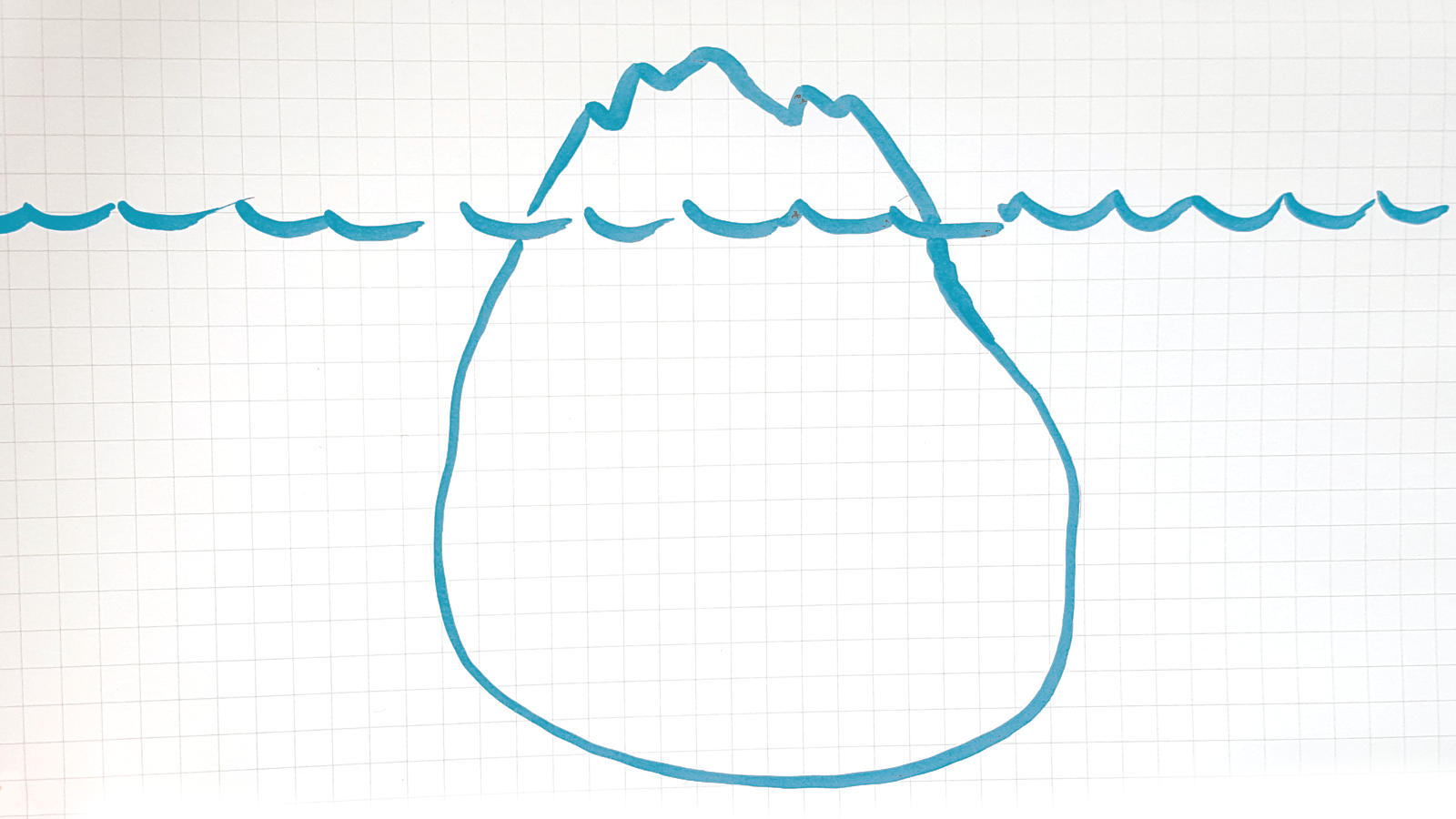

Small groups can maintain a lot of togetherness without much explicit structure. We can hold shared context without needing to agree precisely on the words that describe that context.

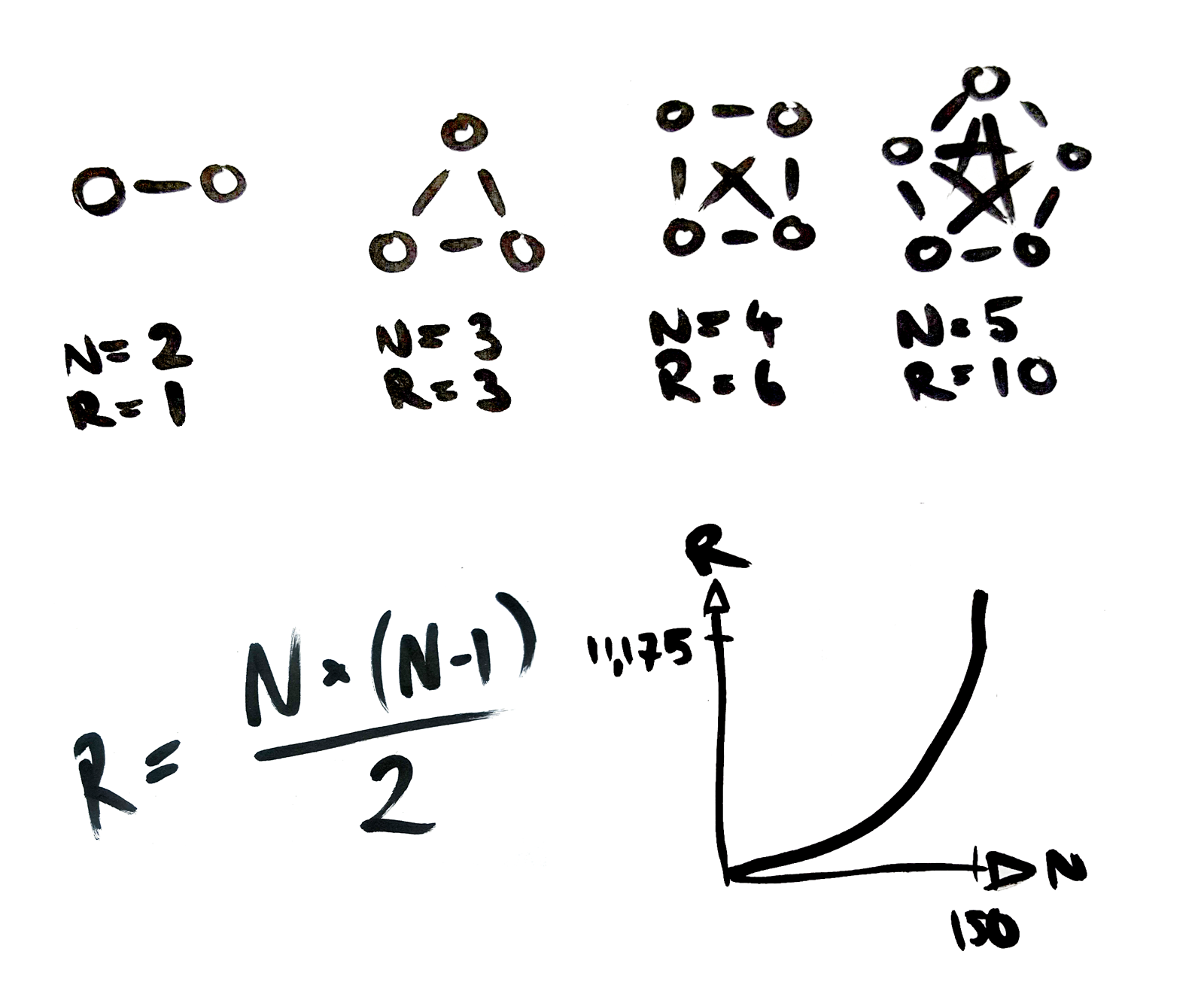

When the group is small, everyone can build peer-to-peer trust bonds with everyone else. It is pretty easy to trust someone once you’ve shared food with them a couple of times, or done some engaging work together, or supported them through a hard day. With a small number of members, it doesn’t take long for everyone to have a coffee date with everyone else. If you have a team of 5, it only takes 10 coffee dates for everyone to get some time together.

Arriving into this high-trust environment, newcomers can accelerate their own trust-building process. If I’m the 6th person to join, and I spend some time with three of the original members and decide I like them, then I can skip ahead to trusting the other two without having much direct interaction with them, because any friend of yours is a friend of mine!

You can have all of this lovely trust and belonging and harmony without having to talk about it. Bonding operates down at the level of your emotions and psychology: we stay together because it feels good to be together. We have a sense of each person’s unique skills and interests. We like each other. We have a shared sense of direction. Notice none of that needs to be written down.

When there’s some tension between people, it’s easy to spot. If the team is made up of emotionally responsive adults, somebody will notice that Tina and Sam are not talking to each other, and will support them to repair the relationship. Everyone can see everyone else. Everyone can know everyone else. Everyone can fit around a dinner table and have a conversation. So you don’t need to formalise a lot of processes or make explicit agreements.

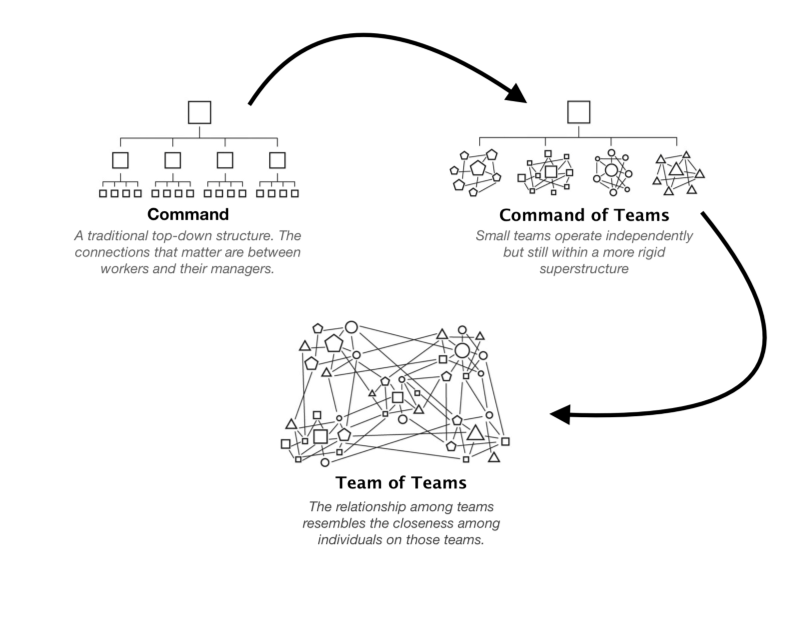

But this lovely easy harmony is impossible to maintain with many more people. Once your group grows bigger than a dinner table, you need to introduce some scaffolding to maintain the togetherness. If you have a team of 5, everyone could have a 1-on-1 conversation with each other member, and it would only take 10 meetings for everyone to see everyone. You can do this over a weekend retreat or a roadtrip. For 30 people that leaps to 429 meetings. 150 people: 11,175 coffee dates. This unavoidable algebra makes big groups much more challenging than small groups.

Bigger groups require more structure to keep them together

At a certain size we start making explicit structures to keep the group together, because it’s cognitively impossible for everyone to maintain a lot of context about everyone else.

Usually, this “explicit structure” comes in the form of written agreements, contracts, policies, rules, roles, guidelines, and best practices. In this article I’m going to take a closer look at this legislative approach to creating structure, and ask if “writing things down” is the best we can do.

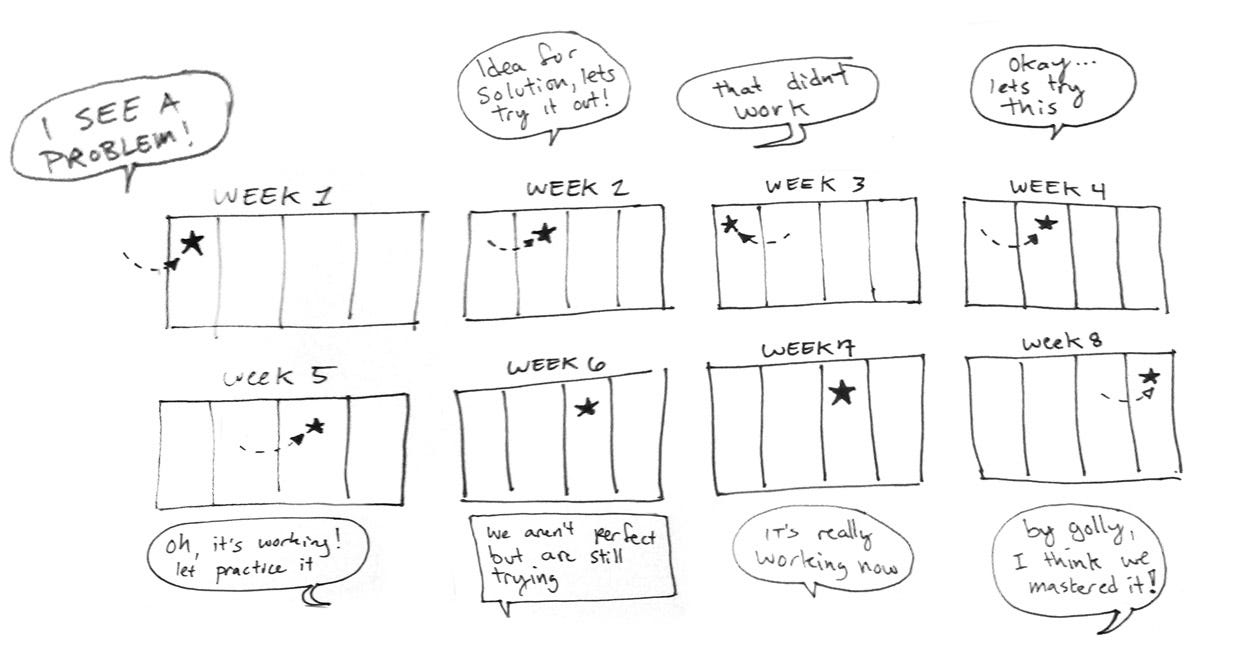

If you review the Enspiral Handbook, or the Gini Handbook or the handbook for any of these hip “future of work” organisations, you’ll see a bunch of roles and rules. These written agreements are the artefacts of deliberations. The deliberations follow a general pattern, something like:

- something harmful or frustrating happens

- people in the group talk about it

- they grow a shared understanding of the problem

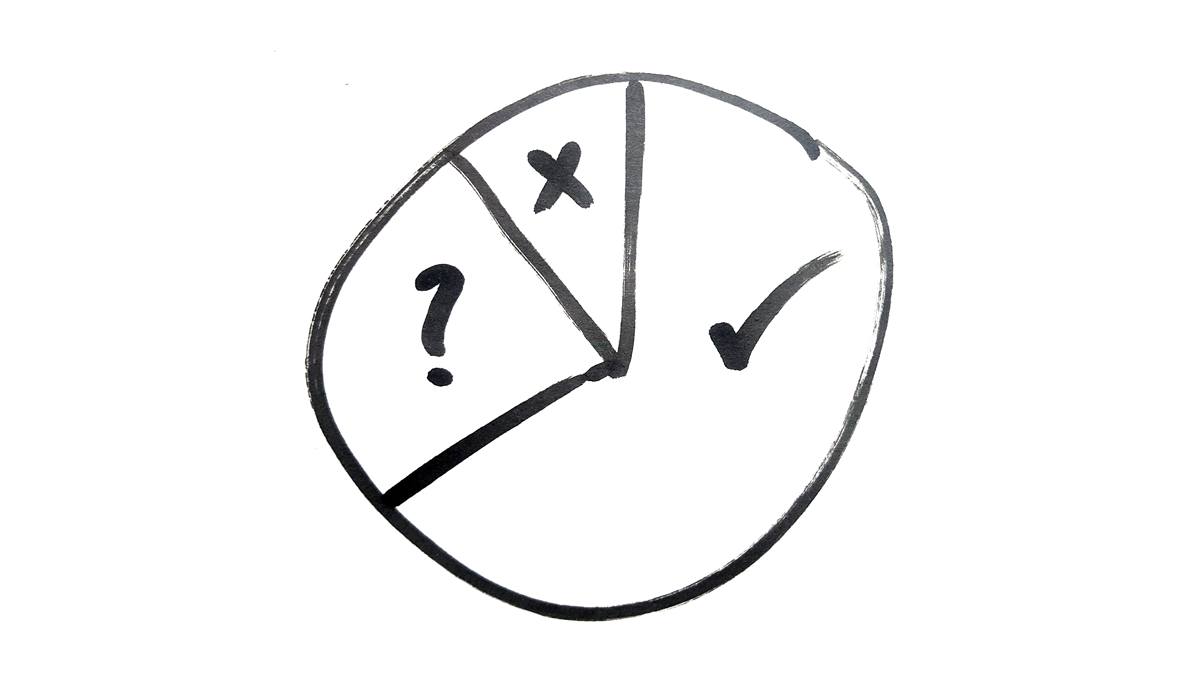

- people suggest different possible responses

- we evaluate the possibilities, collectively running a complex simulation (if we agree to this, what might happen next?)

- then finally, we decide on a response

When we talk through a problem, sometimes the response requires no action, like “that restaurant was crap, let’s not go there again”. Most of the time though, the response is a new piece of structure: you agree to a set of Restaurant Selection Criteria (rules), or appoint the Restaurant Selection Working Group (roles). I’ll jump to a real example to give you the flavour:

Story 1: Don’t feed the trolls

Right now I’m involved in a deliberation about a software project called Scuttlebutt. The founder Dominic Tarr was gifted $200,000 (thanks Dfinity!) to work on this ambitious community-driven project. Dominic decided to break up that big dose of money and distribute it in a series of $5k grants, available to anyone who wants to help grow the ecosystem. Grant-making decisions are made with community input, up to 4 grants per month.

A few months in, after allocating 10 or 15 grants, one of the community members suggests a “pause and review” to check how well the process is working. There’s a big discussion, lots of people taking lots of time to write out their thoughts and consider the ideas of others.

Here’s my summary of the conversation so far: essentially everyone is saying “this is the best grants process I’ve ever participated in”, with a bit of “we could improve this or that detail”. Everyone that is, apart from one person, who alternates between trolling, insulting people, making incoherent arguments, demanding attention, and not listening.

So now we’re at a crucial point in the development of the community. Can we collectively agree that “don’t be a dick” is a good enough principle to keep the grant-making process running smoothly? Or do we need to make an explicit written agreement about what behaviour is appropriate? — Join me on Scuttlebutt if you want to see how this plays out!